[First Appeared in Kyoto Journal 108]

*Italicized words are found texts from actual wine reviews

* Italicized words borrowed from Tonline wine reviews.

This might be challenging at first. I know it was for me. Having spent my adult life in Japan, I was a beer drinker. Cold beer tastes great with Japanese food. Not to mention, the wine we could afford in Tokyo back in those days was undrinkable. Grape bombs from Napa. Not only did they go terribly with the food, but I dislike sweet beverages. And Napa wines gush sweet.

This all changed later in my life when I started traveling to France and Italy, where I learned to appreciate wine. And strangely, wine tasting reminded me of experiences back in Japan, the customs surrounding wine, I mean. The way we slowed down to swirl, sniff and sip... There is an attentiveness to the heightened moment that brought back my time studying tea ceremony, where everyone in the tea room becomes an accidental connoisseur.

Some people say that tea ceremony evolved out of the connoisseurship of Chinese ceramics, while others claim it was most strongly influenced by concepts of mindfulness in Zen Buddhism. All, I can say is—much like in wine tasting—participants learn to slow down and become attentive to details. And being able to speak about personal predilections and taste is an important facet of the study of tea.

I sometimes wonder: have we Americans become so accustomed to food analogies, food pairings, and tasting wheels that we can hardly imagine other ways of talking about wine?

Sometimes it feels like it’s all about sweetness and vigor:

Morello cherry, black cherry, raspberry, marzipan, licorice, and delicate floral notes. Elegant, yet powerful. Complex. Very

long finish.

Of course, for “the guys,” there is also

bacon and molasses; tobacco and leather.

Other times, we speak of spices:

Cinnamon and cardamom, chai, oak and vanilla, cedar, and cigars...

I wonder if that is part of the fun of tasting, to imagine oneself in a pastoral dream of berries, figs, and raisins. Or perhaps a tropical wonderland of lychees, pineapple, and mangosteen.

But what if I told you that it wasn’t always like this? In decades past, Americans talked about wine like the Europeans, in terms of gender and class. Even now, the Italians have grand old dames (Amarone) or the king (Barolo) and the queen (Barbaresco). The legendary Italian wine maker Angelo Gaja described grapes in terms of personality:

Cabernet is to John Wayne as Nebbiolo is to Marcello Mastroianni. Cabernet has a strong personality, open, easily understood and dominating. If Cabernet were a man, he would do his duty every night in the bedroom, but always in the same way. Nebbiolo, on the other hand, would be the brooding, quiet man in the corner, harder to understand but infinitely more complex.

And, of course, there were wines of distinction, and of great lineage and stateliness. Those were to be found primarily in Burgundy. That’s what most people used to say, at least.

Unless you are Kingsley Amis, who thought the whites of Burgundy resembled nothing more than a blend of cold chalk soup and alum cordial with an additive or two to bring it to the color of children’s pee.

It wasn’t until the relatively recent rise of California wines with the Big Boys over at UC Davis’ Department of Viticulture that we got this new, supposedly “scientific” language of the tasting wheel. But is it scientific? I mean, are you sure that when you say “It tastes like a peach” that every peach tastes the same, or everyone else tastes a peach the same way you do? Peaches are tough enough to pin down, but what about fuzzy figs and gushing oranges, candied cherries or Asian pears...

Are you getting hungry?

Maybe not, if you think a wine is

redolent of chicken droppings, like biting into a bar of soap, or tastes of burnt rubber, sulfur, and rot.

Or a dead ringer for cough syrup, just not as tasty.

According to Mark Twain, Germans are exceedingly fond of Rhine wines:

One tells them from vinegar by the label.

My own favorite is DH Lawrence in a letter to Rhys Davis, Apr 25, 1929, who described Spanish wine as:

Foul. Catpiss is Champagne compared, this is the sulphurous urination of some aged horse.

My question is how he knew what cat piss tasted like? Or the urination of an aged horse?

Okay, let me ask you this: how well can you recall the way a wine tastes after the bottle is finished? When you say it “tastes like sour cherries and dried mangoes” does that stick in your mind very long? I could never recall what the wines I drank tasted like, even a day later. This is why I decided to try to talk about wine in a new way.

And I took my lead from the world of tea ceremony.

The tea ceremony lessons had been my first husband Tetsuya’s idea. I wanted to take up a martial art, like kendo or karate.

“No, you are already dangerous enough without a weapon!” he said, chuckling.

“Anyway, all proper Japanese ladies study tea.”

Tetsuya didn’t know this when he suggested it, but my earliest interest in Japan had been the tea ceremony. I was a philosophy major at UC Berkeley, struggling through Being and Time. My professor was a renowned Heidegger scholar, who was himself very interested in Japan. In one of his lectures, he was trying to explain the way our “understanding of being” can be uncovered in our everyday practices. Americans, for example, see the human condition in terms of productivity. That is the ultimate aim, he said. In Heideggerian terms, all of the world is seen as a resource to be used—even our very selves.

To make his point he asked us to consider the Japanese tea ceremony.

“In Japan, to make a bowl of tea, a person must study for years. The ceremony takes approximately forty- five minutes, and every movement is constrained to evoke a perfect moment with friends in the tearoom. Nothing about this practice can be seen as productive or efficient. What do we have for tea in America?”

My professor mischievously scanned the room to see if any of his students would venture a guess.

“Come on, we stick a tea bag in a Styrofoam cup, put it in the microwave and wait a few seconds—then ‘ching’— tea time!”

Everyone laughed.

On my first day of lessons a decade later, I was nervous. I would have to use very polite Japanese (“better just to keep quiet,” my husband suggested helpfully). I would also have to sit in the formal posture of seiza for hours. Before my legs went completely numb and my brain turned off, I managed to examine the scroll in the alcove. Hanging behind some beautifully arranged flowers in a bamboo basket, it read:

一期一会 (ichi-go ichi-e)

Roughly meaning “One time, one encounter,” the phrase evokes the preciousness of every moment. This was a sentiment brought up again and again in tea. For every occasion was a meeting of friends, in a particular time and place—in a specific season with unique weather on that day. My tea friends all kept tea journals, not so unlike my wine journal now, to capture some of the details of those precious moments. Not how the tea tasted or appeared, but rather the sounds, smells and visual splendors of the tea room, topics of formalized conversation and of course seasonal references, including poetry.

The basic idea was that a better appreciation of the seasons and craftsmanship of the ceramics and calligraphy in the hanging scroll—even in being able to notice details about the incense—would be a practice of character cultivation. Not only would we be refining our tastes, but were developing greater equanimity as well. Anyway, that was the idea.

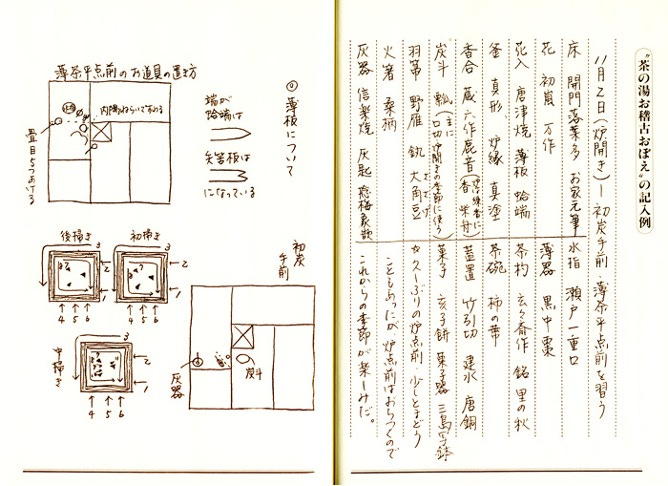

My own tea journal was a version of this one above, where notes were taken on the right side of the page about the items used and displayed in the tearoom that day—while the left side is a diagram of how things should be laid out. For example, on November 2, on the first tea of the sunken hearth season orro-biraki, there are camellias in a rustic stoneware vase in the alcove, beneath calligraphy written by the Grand Tea Master that reads 開門落葉多 (opening the gate, many fallen leaves). This is the second half of a poem about how listening to the sound of rain falling all night is like opening the gate to a pile of fallen leaves. A perfect choice for the season of cold rain and trees shedding their leaves as the world braces itself for the great cold to come.

From the rough feel of the bowl, evoking the color of dried persimmons, to the autumnal name of the incense container—the sound of calling deer— everything works to create a mood for the gathering. And that mood is what is memorable. In the journal entry, there is no mention of the appearance or taste of the tea, instead, the student remarks that she is looking forward to the deepening calm of the season.

My new husband is a Caltech astrophysicist, and in our house we talk about physicist Richard Feynman a lot... but it was only when I read his thoughts on wine that I appreciated how brilliant Feynman was. He suggested that within a glass of wine “are the things of physics: the twisting liquid which evaporates depending on the wind and weather, the reflection in the glass; and our imagination adds atoms. The glass is a distillation of the earth's rocks, and in its composition we see the secrets of the universe's age, and the evolution of stars.”

So Richard Feynman, just like a Japanese tea master discovering the world in a bowl of tea, finds the entire universe reflected in his wine glass. How wonderful it must be to hold your wine glass up to the light and see stars and galaxies refracted there! And I do think that happiness demands this kind of slowing down. When you slow down and become attentive to the world, you come to belong to the world as much as the world belongs to you—even if just in that moment. The world is no longer a resource to be efficiently consumed, but instead becomes filled with meaning and lit up in beauty.

Happiness, as Marcel Proust suggested, demands an attunement of oneself to the local environment—and to place (terroir). When a person takes the time to stop and linger, an hour is not merely an hour but rather is “a vase filled with perfumes, sounds, places and climates! ... So we hold within us a treasure of impressions, clustered in small knots, each with a flavor of its own, formed from our own experiences, that become certain moments of our past.”

Life is a constant shuffling of the deck, and each and every tea gathering was precious and unique, a once in a lifetime combination of people, utensils and experiences. Never again would the same group come together to drink tea in a room with just that particular combination of hanging scroll, blend of tea, fragrance of incense; with that one-of-a-kind arrangement of flowers (appearing in the vessel “as if growing in a field...”)—the tea bowl and the brazier; the colors of my friends’ kimono and the quality of our laughter that day.

This slowing down, savoring, and noticing is not something inherent to tea, but rather is an intentionality that we can bring to many activities. And so I tried with wine. The hardest part for me was trying not to compare a bottle of wine to any other flavor of food. That is more challenging than it sounds. I keep a journal and always remark about the season and the company. Also what food was served and maybe what music was playing. Sometimes, I even try to cultivate and refine my senses by comparing the wine to a Japanese poem or to paintings in the Louvre. Imagining them on the wall.

A grand crus from the Côte de Beaune is the Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele by Jan van Eyck.

Or this Amarone della Valpolicella that I’ve been saving for Christmas is the Madonna della Vittoria by Mantegna.

You can choose whatever you like. My husband—the ever-competitive astrophysicist—suggested our wine tastings involve speaking in terms of stars and galaxies.

Yes!

'The whole universe is in a glass of wine,' said Richard Feynman. It’s true. Why limit yourself to berries?

Optional link to my Mini-Syllabus : How to Talk about Wine like a Japanese Tea Master HERE

Absolutely loved this! So full of wisdom, entertainment and food for thought. My husband used to talk about Richard Feynman a lot, but now that he is retired and we are living in the 'wine state' I can see a different angle for him.

You are so right about the language of wine-tasting. I think those fruity, veggie, flowery adjectives all derive from that dreaded misnomer 'bouquet', as though one had chomped on a handful of flowers blindfolded, and were required to 'name that blossom'. But what I love about your description of the tea ceremony was the emphasis on the process, on the event itself at a particular place in time, rather than the dissection of the taste of tea itself. This coupling of process with content is what contributes to how tea tasted that one time--not to be compared with all the other times when the circumstances were different. This is a kind of connoisseurship that requires paying close attention to the smallest details. A wonderful post.