1.

In the prologue to his new book, The Forger’s Creed, art historian J.P Park tells the incredible story of the time that legendary Berkeley art historian James Cahill, while still a grad student at the University of Michigan, conceived of a project to replicate a Ming dynasty literati painting. The occasion was his advisor Max Loehr’s 88th birthday. And he wanted to blow his mind.

First, he needed someone to paint the picture. But he had a friend who fit the bill. The painter and art professor William Lewis had expressed an interest to Cahill about wanting to learn Chinese ink painting techniques, so Cahill provided him with a copy of the famous Mustard Seed Manual of Painting as a guide to Chinese styles— along with some ink and an inkstone.

Lewis immediately got to work.

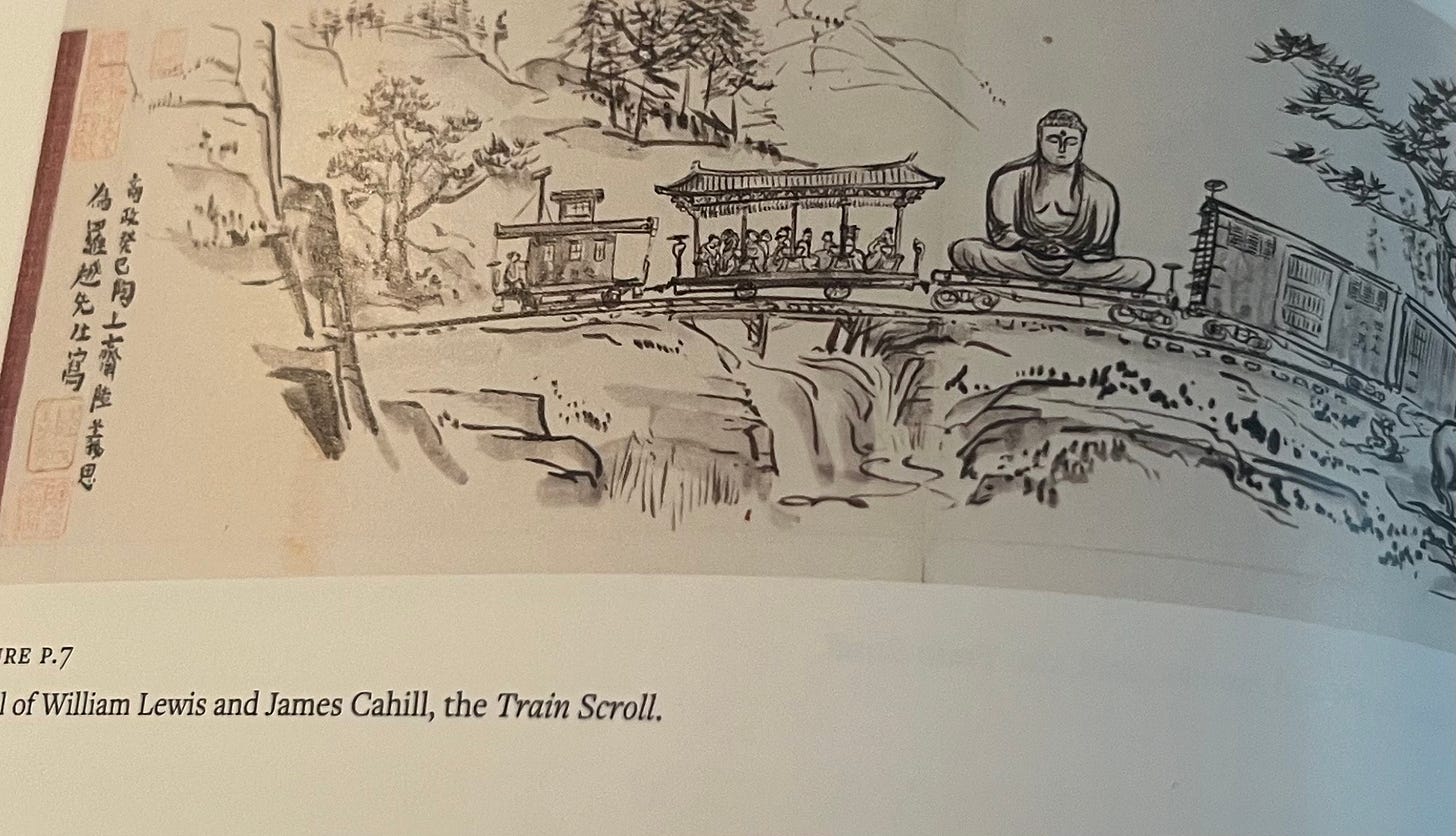

I might not be allowed to post these photos (below bottom), which I took with my iPhone from Parks’s fantastic book, but I wanted to share the way Lewis created an American train chugging through a Chinese landscape. Or I should say landscapes. Traveling through the scroll, we find each scene is painted in a different style of painting (like you can see the Mi Family dot style on those conical mountains to the left and further on is a “Ma Yuan composition gone wrong.”)

So, the Train Scroll is less a copy, as it is a homage—though Park uses it in his book on forgery in China to make the point that copying and creating homages is a time-honored practice in China — as artists all learn by copying.

(In Japan, this is true in calligraphy and painting and also true for dance, tea and ikebana).

2.

Think about Chang Dai-Cheng (Zhang Daqian), who was arguably the greatest Chinese painter to come along in centuries. Before his death in the early 1980’s, Chang had painted countless masterpieces, was known as the Chinese Picasso, was a renown seal carver and poet—not to mention one of the most successful art forgers in modern history! About twenty-five years ago, there was a symposium at the MET devoted to a possible Chang-forgery that had infiltrated their own collection! The famous Riverbank —attributed to Dong Yuan.

In China, to copy the work of the Old Masters is not considered a strictly criminal activity as it would be by the curators at the MET. In an article from 1999 in the NYTimes, Holland Cutter writes that,

Authenticity means different things in different cultures. In Western art, the original -- the unique object, the genius creator -- is everything. And a conceptual, even legal understanding of the distinctions between the original and a copy, and a copy and a forgery, is clear cut. In Chinese painting, by contrast, tradition predominates over individuality (though that is also prized). And the concept of authenticity, of what constitutes the genuine article, is more nuanced.

And:

As a medium, ink-and-brush painting on silk or paper is evanescent, and relatively few early examples survive. As a result, Chinese artists, in what amounts to a kind of centuries-long collective archiving process, have copied and recopied revered works, and many of these copies have come to be regarded as masterpieces in themselves.

This reminds me of the Shrine at Ise, a kind of Ship of Theseus, where identity remains even if the original object is lost.

3.

But back to the Train Scroll.

In addition to Lewis’s playful homage to the history of Chinese literati painting, Cahill actually brushed numerous colophons in the empty space of the scroll, celebrating the importance of this “work.” He emulated the calligraphy of Mi Fu and Emperor Huizong and even hit up a few friends from the university to create poems and other works of calligraphy. You can see a Japanese poem in exquisite calligraphy in the picture below.

Cahill was still quite young when he did this! How did he manage all that gorgeous calligraphy?

When the work was presented to his esteemed advisor, the professor held the scroll in both hands and read aloud with great flair all the poetry and commentary on the scroll for those who had gathered. According to Park, and I agree, by turning the material object into an event with multiple collaborators and actors, more than anything else, Cahill illuminated the experience of literati art in the ming dynasty.

I think this is a useful way to understand pre-modern aristocratic art in Japan as well.

++

The Forger's Creed : Reinventing Art History in Early Modern China, by J.P Park

Forged: Why Fakes Are the Great Art of Our Age by Jonathon Keats – review

Issues of Authenticity in Chinese Art: Papers Prepared for an International Symposium Organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Wonderful

Wow, fascinating topic! Thank you for the images, too. I liked the comment about Ise; so many “ancient” structures in Japan have been rebuilt regularly. I can’t do Ise this time, I think it’s a little too out of the way this time, but we’ll see. You always write such fascinating essays!