1.

見るところ花にあらずと云ふことなし、

思ふところ月にあらずと云ふことなし。

There is nothing you can see that is not a flower. Nothing you can think that is not the moon.

Basho, in his notebooks, encourages us to follow the flowers and be ever-mindful of the moon. For this is how we can empty our monkey minds 心猿 (shin’en) and become one with the world. It is also how we can do good art; for he says that when you look at a painting by Sesshu, or read a poem by Saigyo, what you are really seeing is zoka 造化.

Zoka (in Chinese Zaohua) means creation and transformation. It is an ancient Daoist term that Basho became obsessed with during his lifetime. Because he traveled the road with a well-worn copy of the Zhuangzi, never leaving home without it, he knew that in ancient China zoka did not mean “creative” in terms of “creativity.” Nor did it mean “nature” as a world of things and objects. Rather, zoka referred to the generative force of the universe. And Basho, like an ancient Daoist sage sought to become one with this spontaneous and ever-changing force of nature in his poetry.

And so can we.

2.

I recently finished a fantastic book called

Basho and the Dao: The Zhuangzi and the Transformation of Haikai.

Written by a scholar born and educated in China, Peipei Qiu also studied at Columbia University in the US and then at the Japan Foundation, in Japan, both times with Donald Keene. As suggested by the book’s title, Qiu seeks to unravel the Chinese sources found in the early history of Haikai —specifically the Daoist influences on the work of Basho.

An interesting thing to consider, suggests Qiu, is how the Western understanding of “originality” differs from the one prized in East Asia. Unlike the Western conception, which prizes personal expression and newness; in Japan, Qiu writes that traditional artistic appreciation favored originality within the context of the traditional canon.

I think of it like counterpoint. The great artists were adept as creating fresh counterpoints to the past.

不易流行 Fueki ryuko is an expression made famous by Basho and means “the unchanging and the ever-changing.”

Yes, Basho said that to know bamboo one must go to the bamboo. That is true, but knowing will always be in conversation with the traditional canon. And this is why you will not find poems about bamboo in autumn. Or of fireworks and wind-chimes in winter. As Peipei Qiu writes:

“According to the normative essence, when the image of winter rain is used, it signifies specifically shigure, a short shower in early winter, even though there are other kinds of rains in the season. Similarly, the image of spring rain has to be a kind of quiet and misty drizzling.”

3.

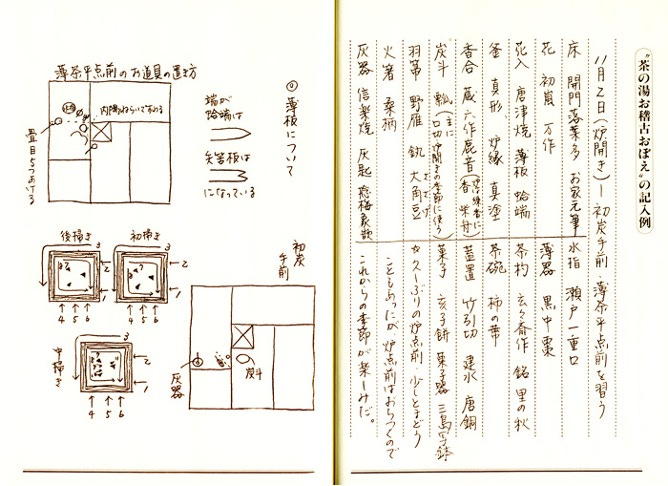

Above is an image of a typical diary used to record lessons in the tea ceremony. Notes are taken on the right side of the page about the items used in the tearoom that day—while the left side is a diagram of how utensils were laid out.

November 2, on the first tea of the sunken hearth season, there are camellias in a rustic stoneware vase in the alcove, beneath calligraphy written by the Grand Tea Master that reads 開門落葉多 (opening the gate, many fallen leaves).

This is actually the second half of a poem about how listening to the sound of rain falling all night is like opening the gate to a pile of fallen leaves. A perfect choice for the season of cold rain and trees shedding their leaves as the world braces itself for the great cold to come.

But the calligraphy wouldn’t work if people in the room didn’t recall the first part of the poem!

The internalization and commitment to the tradition might act as a constraint on personal reactions to things, but it can allow for the intense compression that characterizes Japanese poetry.

I like to think of these intertextual literary associations like the sophons from the novel Three Body Problem, where an 11-dimensional proton can unfold onto a plane of great surface area. Words can be like that. Pregnant. But people need to read the same books, so by definition art was an elite practice for a small population of practioners. In grad school my professor of classical Japanese liked to remind us that the poetry and diaries of the Heian period were shared among only a handful of people. And so, much knowledge was assumed.

4.

One way that Basho found to be avant-garde, according to Peipei Qiu, was in his renewal of the Chinese exemplary models. For example, one of his heroes was one of my heroes, Tao Yuanming 陶淵明.

Not only was Tao Yuanming’s Daoism-infused poetry used as a touchstone for Basho’s own works, but his life as a wandering aesthete-recluse was a model as well.

Xiaoyaoyou 逍遥游 (shōyōyū in Japanese) is the title of the first chapter of the Daoist classic the Zhuangzi. The word Xiaoyaoyou roughly means free and unfettered wandering—but it really points to a mode of being in the world, one whereby the mind is liberated. It is this mindset so often seen in the poetry of Tao Yuanming—one that was so appreciated and idolized by Basho (and by me!) of being free to pluck chrysanthemums by the eastern fence, as the world crazily spins on faraway….

This was the goal of Basho’s journeys— to free the mind and still the heart. Away from people, there is calm, leisure and joy—can you imagine it?

I am a big fan of the work of China scholar and philosopher Roger T. Ames, whose work has aimed to uncover a more authentic understanding of ancient Chinese philosophy. He does this through an analysis of key philosophical terminology, both through an analysis of the etymology of the characters as well as looking at key terms in clusters to try and piece together what the terms must have originally meant. It is hard to see one’s own preconceived notions from within the confines of the language one thinks in. I am not even going as far as the Whorf theory of language… just pointing out that language does order our thoughts and that it is hard enough to try and translate words from modern Chinese, embedded in its own cultural matrix of concepts, much less that of people who are separated from us in time by thousands of years.

To approach what Basho admired in the Daoist term xiaoyaoyu, Qiu says we should think of this free wandering alongside related concepts, such as the “natural and spontaneous” (ziran 自然 shizen in Japanese); wuwei as non-interference, and perhaps my favorite new word of all: xinyou 心遊 the free wandering of mind.

Pictures from my fourth ikebana lesson…

Thank you for this writing and introducing a Chinese perspective to haiku and Japanese aesthetics. I really feel the emergence of a greater appreciation and understanding of the Asian creative instinct. You are certainly a channel for that. 💫🙏💫

I like "xinyou 心遊 the free wandering of mind" the best too! It's the essence of living--at least for me. This post also reminded me of the times I've been disappointed in English. So often words in my adopted language are poetic from the start, without having to be explained. As for types of rain, one of the first words I learned was Schnurregen, or string rain, a specialty in Salzburg.