First published at 3 Quarks Daily

1.

All I wanted, I told him, was “the perfect teapot.” Just one would be enough, I said, but it had to be perfect (1) — as if a teapot could make everything else in the world okay. A seemingly simple task, and yet finding it was elusive as any great chase.

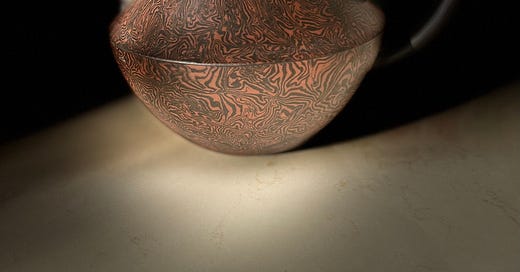

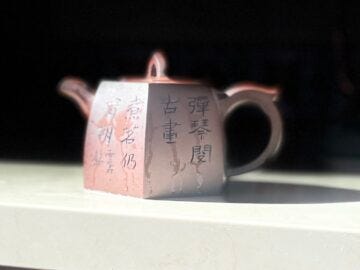

My first demand was it had to be a Yixing zisha teapot. Valued since at least the tenth century in China, zisha pots are purple or reddish-brownish, unglazed stoneware that are so beautiful they will make you drool (2). The first thing I did was spend hours at the Flagstaff Tea Museum in Hong Kong. Studying the pots in their collection, I tried to narrow down exactly what I wanted in my own “perfect pot.” I learned all about the way zisha pots are hand-modeled out of what is extremely hard clay. Like any great Literati art, one artist alone is traditionally in charge of the entire process from start to finish, and therefore the artist’s seal will be affixed to the bottom of the pot as it is in every way that artist’s creation: one of a kind.

It was in Hong Kong where I’d first fallen in love with tea and stoneware pots. Even now, I never cease to marvel at how soft and warm stoneware feels in comparison to porcelain. Handling unglazed pottery is always a very sensual experience; porous and velvety, it’s like human skin. One of the reasons zisha pots are favored by Chinese tea masters is because the clay absorbs the fragrance and taste of the tea and over time the pot brings something of itself to every brewing, like antique oak barrels used for wine or the ground used in certain kinds of pickling.

In East Asia, porcelain is known not by its translucent quality but rather by its resonance. That is why in Japan, when you buy a porcelain tea-set, the shopkeeper will flick each piece to produce a pinging sound, thereby demonstrating to the buyer that yes, this is porcelain. But for my money, nothing is more delightful than the sound a zisha lid makes when united with the teapot. Clack.

After looking at pots for weeks, I decided on darker “purplish-brown” color clay of a geometric or square type, I set out for days on end scouring the shops and galleries of Hollywood Road and Kowloon. I could spend the rest of my life in Hong Kong, and if I did, I would probably end up walking around Hollywood Road most of those days. In the end, I purchased three Yixing pots and two antique dishes shaped like fans, as well a set of teacups and a little water container… this happened slowly over the course of a year’s wandering there.

2.

When I told him that I wanted—no, I needed to find the perfect pot—as if one little pot could make everything else okay, he told me I was like the Song Emperor Huizong with his bronzes.

Born in 1082, as the eleventh prince of Emperor Shenzong, it was never conceived that Huizong would ascend the throne. His early years were therefore full of much freedom which allowed him to pursue his many interests– chief among those the practice and collecting of art. While his older brothers closer in line to the throne were educated and disciplined in statecraft, Confucian political philosophy and the Classics, Huizong was pretty much left alone to dabble in his hobbies. And, by the time he was in his late teens, his literary fame was already known outside the walls of glorious capital.

But a series of mishaps landed him– against the odds—on the throne in 1100. And the timing couldn’t have been worse as invaders were known to be amassing along the border for an invasion.

And, there he was. The country on the brink of disaster and rather than mobilizing the army, he sought instead to throw himself into the study and re-cataloging of the ancient bronzes. As if to say, “If I could just get the bronzes right, everything else would follow suit.” Great archaeological and art historical research– respected even today– was undertaken to both interpret the inscriptions found on the bronzes as well as to properly reconstruct the rituals in which they were used. He did all this, obliviously writing his poetry in his gorgeous handwriting and lavishly spending on the arts as his country teetered on the edge of disaster.

3.

I think when one is facing a terrible dilemma there are 3 possible approaches:

One, you can ignore the problem.

Two, you can face the problem head-on

or

Three, you can seek to eliminate the causes of the problem so that the problem will cease to arise.

His detractors perhaps could accuse Huizong of the first, while those who are fond of him might prefer to posit the third.

4.

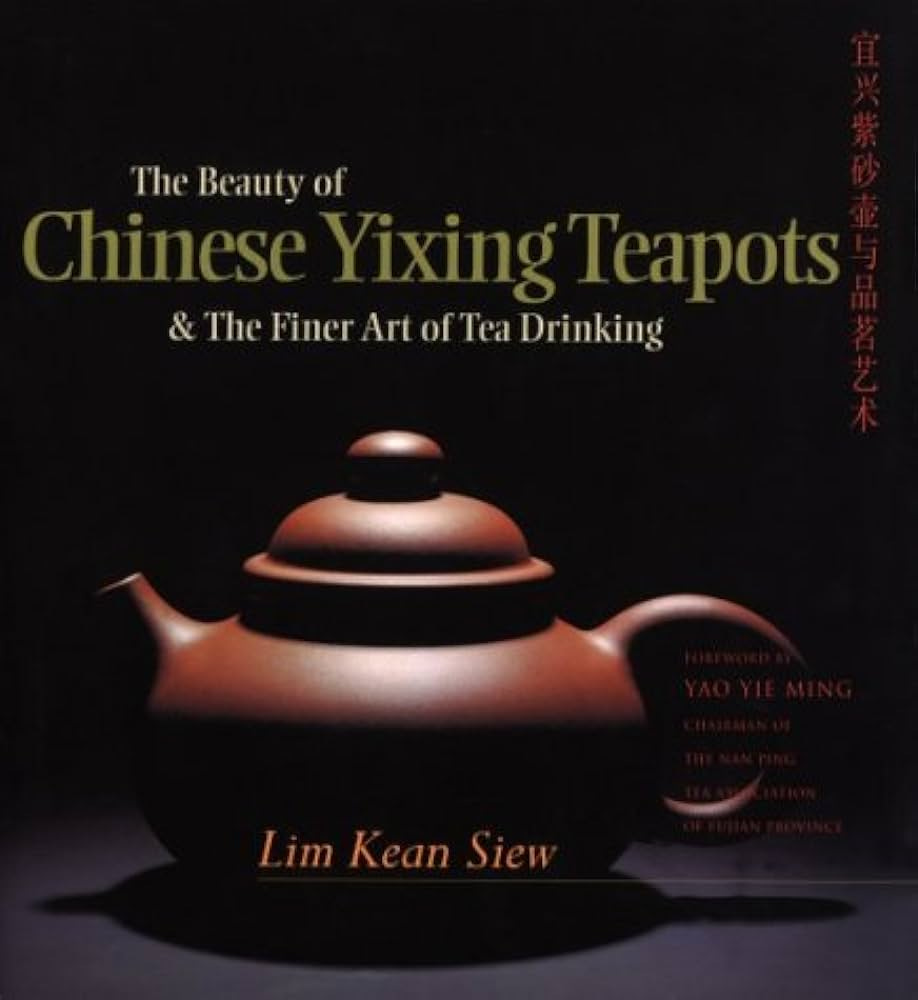

If you’re interested in Zisha, there is a wonderful book called The Beauty of Chinese Yixing Teapots: And the Finer Arts of Tea Drinking, by Lim Kean Siew. The author was a high-powered lawyer and political activist in Malaysia back in the day, and if that wasn’t enough, upon his retirement he decided to undertake a scientific study of his massive collection of teapots. Our man in Penang not only embarked on a study of his collection but set about to dash all the codified notions concerning teapots that had ruled Chinese tea drinking habits for over a thousand years.

Like all cultural practices, these codified rules concerning tea preparation are so much taken for granted that people don’t seem to think twice about them: like red earthenware pots for oolong, darker pots for puerh, and green tea in porcelain or glass teapots. Lim asked the obvious question, why? Was there some reason informing these rules or does it just come down to preference? Setting out to uncover the answer, he went about his task by scientific experiment.

He first outlined his methodological principles:

All of his pots would come from a government factory in Yixing itself, choosing the Yixing Zisha Factory #1 — where quality and standards were tightly controlled. He could, in this way, be assured that we were talking of real Yixing of a certain knowable standard. His pots ranged from works of art created by living national treasures to simpler, more humble pots– but all were guaranteed Yixing “purple sand” clay 宜興紫砂.

In addition, all his teas would be of the highest quality. Water would be standardized. Non-hard tap water. Tea would always be prepared in the same manner and he, along with a variety of tea connoisseurs, would observe– which pots went with which teas.

So, what did he uncover in all his experiments? Well, first of all, that green tea can indeed be made using Yixing ware. And, puerh doesn’t taste any better with darker purple clay pots. Smaller pots are not a necessity for tie guanyin either. He tells us, “One must be reasonable,” and urges us to look at the teapots themselves. For his experiments proved that just as tea connoisseurs have been telling us for a thousand years, the teapots themselves will inform you what tea should or should not be used. The wrong tea, a thousand years of tea teachers have instructed, will make a teapot turn pale and dry. And it will give us a less than perfect cup of tea. Earthenware– like skin– does react to heat and chemicals in the tea by changing tone or color– it is visible to anyone using such a pot, and Lim-sensei urges us to stop and taking a deep breath, take a good hard look—and listen to what these miraculous pots have to tell us!

Notes:

(1) Roland Barthes in his Lover’s Discourse describes this perception of perfection using the word “adorable!” The object is loved in their entirety– a state which no word can describe. For want of a better word, Barthes calls this adorable! I call it perfection which is to say, I love you because I love you– “not for one or another of [their] qualities, but for everything!” “By a singular logic, the amorous subject perceives the other as a Whole (in the fashion of Paris on an autumn afternoon), and, at the same time, it involves a remainder, which he cannot express. It is the other as a whole who produces in him an aesthetic vision: he praises the other for being perfect, he glorifies himself for having chosen this perfect other; he imagines that the other wants to be loves, as he himself wants to be loved, not for one or another of his qualities, but for everything, and this everything, he bestows upon the other in the form of a blank word: Adorable!”– Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse

(2) Back in California, I hardly use my teapots anymore. Mainly because the water is so bad and even using filtered, the tea never tastes the same. If you like tea, I highly recommend two from the Tea Dealers in New York: this Shou and this Sheng. Whatever you do, avoid looking at their zisha pots since they will make you drool with desire.

This guy I used to know online used to email every once in awhile, and to try and catch up with me, he’d always ask, “so what are you drooling over these days?” I found it to be very much the point.

(3) One of the sweetest books I read in 2023 was Vera Wong’s Unsolicited Advice for Murderers, by Jesse Q. Sutanto. The author was on my radar because one of the bookclubs at Caltech that I don’t participate in but follow read her Dial A for Aunties, and when I found out that this book had a tea theme, I could not resist and I loved it. I sent it to my son but he was not as amused and said that pesky Vera Wong reminded him of me!

(4) And if you are interested, here is an essay I wrote about Christopher Hitchens and a Korean Teabowl.

(Of course, the water comes off your roof into the tank.)

I mostly drink coffee (caffeine addiction) although I also drink tea (made with tea bags). Pu-erh is a good solution. Strong earthy flavour blends well with strong-tasting water.

Of course you can get rainwater tanks in California. Just google them. We’re talking about something a reasonable size. I’m sure they would cost a bit and require some space next to the house, but it’s wonderful to have your own supply of drinkable water, totally separate from town water. No chemicals, just clean, fresh water. Every time it rains you think: “Wonderful, I can just hear my tank filling up!” (Not so good if you don’t have access to town water and there’s a drought! But I like drinking tank water.)