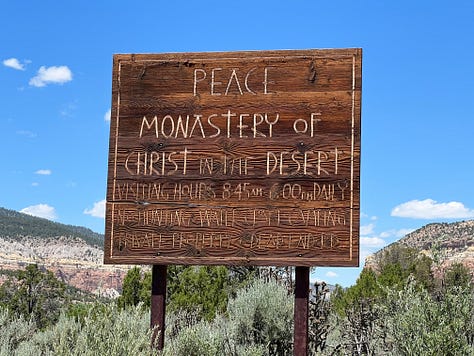

In 2019, Fred Bahnson wrote an unforgettable essay in Emergence Magazine about Thomas Merton’s 1968 trip to the American West. It was an early journey made by the monk from his spiritual home in Kentucky at the Gethsemane Abbey —first to the Redwoods Monastery in Whitethorn, California, then on to the Monastery of Christ in the Desert in Abiquiu, New Mexico.

Travel is a metaphor for the greater spiritual journey itself, wrote Merton. A pilgrimage is not trying to do anything, he says, but just trying to be.

Merton was a great lover of redwood trees and the desert. When he visited the monastery at Abiquiu, it was newly built and just getting going. He described it like this: “In America, there is no monastic foundation which has found so perfect a desert setting as that of the Chama Canyon, in New Mexico.… The place was chosen with careful deliberation, and it is admirable.”

By the time Bahnson arrived in 2019, the monks had made the desert bloom.

Living entirely off-grid using the largest private solar power farm in New Mexico, they grow peonies and vegetables and hops for making their own beer. People can stay there on retreat—where they hike and study—soaking in the silence. And just as in Merton’s day, they keep to the schedule of prayer… some four hours a day, 365 days a year. I have a friend, not Catholic, who liked to go on such retreats here in California every year or so. Like Pico Iyer at the Monastery in Big Sur, she also finds it fruitful to sit in silence. (I hear that Pico Iyer’s next book will be abut the Catholic Monastery where he has been going on retreat for thirty years in Big Sur).

Ever since reading Bahnson’s essay, I’d been hoping to see Monastery of Christ in the Desert. The first time I was in Abiquiu, the Monastery was closed because of Covid. I tried to read what I could about the place and was delighted to find it mentioned in a book I keep mentioning in these pages, the SONOROUS DESERT BY KIM HAINES-EITZEN. As Haines-Eitzen writes, the history of Christianity really begins with the desert fathers, living in solitude away from the loud bustle of the world out in the deserts of Egypt and the Levant. But it wasn’t just the early Christians, for throughout history, she writes, there has been an idea of the riches that are to be found in silence:

There is another idea about silence in the monastic literature that moves beyond not speaking. Here a multivalent Greek word becomes essential to understanding monastic silence: hesychia, which could mean “silence,” “solitude,” “quiet,” or “stillness.” It was, and is, a simple word that took on deep significance for Christian monasticism in the eastern Mediterranean. Hesychia was contrasted with disturbance: practicing hesychia or living in hesychia meant freedom from disturbance—disturbance of noise, disturbance of distraction, the interruptions of sound. There are stories, for example, of monks who say, “The ones who pray to God should make their prayers in peace and hesychia and much tranquility.” Essential to the idea of hesychia is a dualism: the inner and outer qualities of stillness and quiet. It required monks to reflect on how to develop inner quietude in the midst of a noisy and distracting world. This question was at the heart of the monastic endeavor.

++

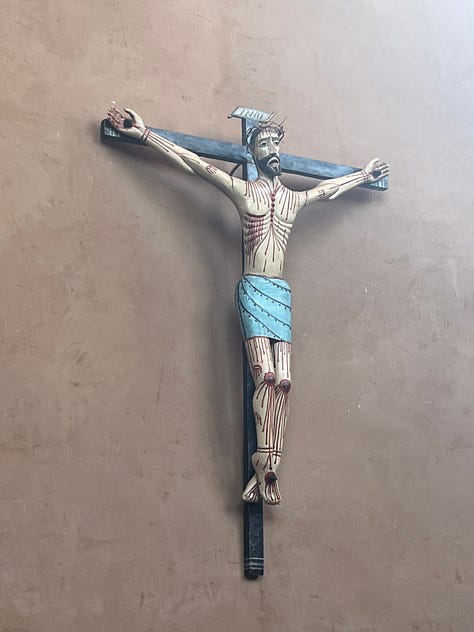

Finally, traveling out there last week, I tried to soak up the sounds— the flowing water of the muddy Chama River and the wind in the pines. The loudest sound was the relentless rhythm of the clicky bugs punctuated by the squeaking sound of the ash-throated flycatchers. It is only 15 miles from Ghost Ranch, made famous by georgia O’Keeffe. But it takes nearly an hour to travel there on unpaved very rough roads that road along side the flowing Chama River. Arriving in a cloud of dust, it feels like a tiny shangri-la, seeing the horses and green fields, the church bells and three crosses on the top of the mountain. It reminded me of a small replica of Montserrat in Catalonia with those red cliffs pressing down on top of the monastery.

I’ve never been on a retreat—have never sat quietly or walked alone like my friend does every year. I am looking forward to reading Iyer’s book when it comes out.

The beautiful, eleven-minute movie that was made by Jeremy Seifert On The Road With Thomas Merton to accompany Bahnson’s essay in Emergence is here— highly recommend it!

Beautiful film! Merton is a gem. I'll have to look up one of my favorite quotes from him when I have access to my books (I'm with my cousin). He refers to the wind in the pine trees. I think that the pine trees have always represented all those modes of silence, stillness, and solitude for me. Thank you so much for writing this piece, Leanne!