Traduttore, Traditore

RF Kuang's Babel: Or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators' Revolution

1.

After finishing RF Kuang’s latest novel Yellowface, which my friend Barb describes as a cautionary tale about the perils of the publishing industry, I decided to go back and re-read her second book (her magnum opus?) Babel: Or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators' Revolution.

I am still obsessively reading novels with protagonists who are translators —favorites remain Katie Kitamura’s A Separation and Idra Novey’s Ways to Disappear.

To these, I would add Babel.

Set in a speculative 1830s Britain, the novel follows a Chinese-born boy who is adopted and brought to Victorian England by a mysterious and eerie professor. And there, after an intense regime of language study (Greek and Latin) he is enrolled in Oxford’s Royal Institute of Translation (nicknamed Babel). Students enrolled in the translation program are the elite of the elite at Oxford—and they represent many of the world’s languages—making for a more multi-cultural student body.

In an introductory lecture, one of the professors lays out the crucial problem that translators have always faced:

“Translators are always being accused of faithlessness…. Fidelity to whom? The text? The audience? The author? …. Is faithful translation impossible, then? But what is the opposite of fidelity? Betrayal. Translation means doing violence upon the original, means warping and distorting it for foreign, unintended eyes. So then where does that leave us? How can we conclude, except by acknowledging that an act of translation is then necessarily always an act of betrayal?”

And if “fidelity” is the issue, then to whom? To the writer? Or perhaps to the reader…?

Another professor later brings up something Dryden wrote about the Aeneid. “I have endeavoured to make Virgil speak such English as he would himself have spoken, if he had been born in England, and in this present age.’

But do we really want an Aeneas in tweed jackets drinking earl gray tea? This is reminiscent of Waley’s translation of Genji, in which so much of the time and place of the original work has been replaced by Victorian English culture and conventions.

Should a translation be seamless? Or should there be a stiffness or foreign flavor so readers don’t forget the original language was different than the one in which they are presently reading? For example, in Adriana Hunter’s translation from French of The Anomaly by Hervé Le Tellier, she directly translates a bit of interiority where a french speaker is thinking of polite and casual forms of “you.” Bot something a person would think in English, this immediately alerts readers that we are reading a translation…. Oh yeah, the character is thinking in French. That could have been handled differently for better or worse depending on your preference for things like this.

2.

The English word translation derives from the Latin word translatio, which comes from trans, "across" + ferre, "to carry" or "to bring" (-latio in turn coming from latus, the past participle of ferre). It conveys movement, distance even (such as the translation of relics).

Japanese, meanwhile, has connotations of turning or flipping something over.

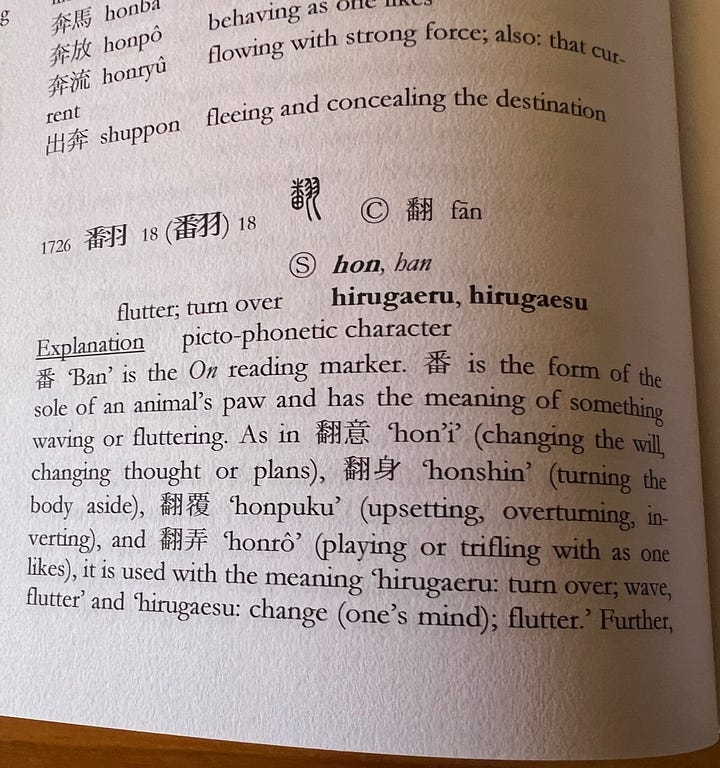

翻訳 honyaku

In the first character hon 翻, you can see the wings 羽 right there for the fluttering and turning, flipping quality; while the second character “yaku” 訳 conveys meaning and sense.

This word sense immediately brings to mind something Cicero (or Horace?) wrote about aiming for sense translation, rather than a word for word translation.

non verbum e verbo sed sensum de sensu

This is because languages do not divide the world up the same way. If they did, AI translation would be a done deal already. (In the novel, a professor lectures them on the dangers of the word for hello, and how its use differs wildly between languages, making even so simple a word fraught with choices).

Returning back to the word translation itself, in Japanese, the difference between interpretation and translation is much more strictly differentiated then it is in English. In Japanese, to interpret (verbally) is tsuuyaku 通訳 while to translate (texts) is honyaku 翻訳. In English the terms of conflated or not carefully defined and most linguists could be called translators, whether working in texts or working verbally in the courts for example. Not so in Japanese.

Also in Japanese, the difference between a direct word-for-word translation 直訳 chokuyaku and a more literary “sense” translation 意訳 iyaku, are not considered particularly technical. And translations that have precedents legally or even on the Internet are called 定訳 teiyaku, or the regular or official translation.

It is these gaps in meanings of words (informing different understandings of being) that fuel the speculative magic of the novel. Not just that there are different words for “translation” in English and Japanese but the etymologies bring vastly different nuances, as do the cultural use of the language itself. It sounds confusing but it is this gap which imparts magical power to the silver bars being produced on the top floor of the tower (see the picture at top)— and this is incredibly lucrative fueling the entire imperial program.

++

I love this novel and want to write more about it! I will also be posting about Kuang’s Yellowface in the coming week. Also, read and loved The Anomaly by Hervé Le Tellier (translated by Adriana Hunter).

See Claire Chamber’s essay on Babel at 3 Quarks Daily Translation as Colonialism’s Engine Fuel

Chicago Review of Books review by Daniel Rabuzzi: Translation as Oppression and Liberation

For more: please see my 3QD Essay Translating Plum Blossoms 宋徽宗〈蠟梅山禽〉

oh and p.s. I find that 翻る character super annoying, it was in my kanji-learning app a couple of levels back and I keep getting it wrong! So funny that you mentioned it. I do feel that 翻る has the sense of being flipped over or toppled somehow. I think it's the sound of the word. I also keep mixing it up with 覆る, which also has the sense of being flipped over. I love that 翻 is in the word for translation, though, it feels so right.

Great post! I recently read the book myself and loved its observations about translation.