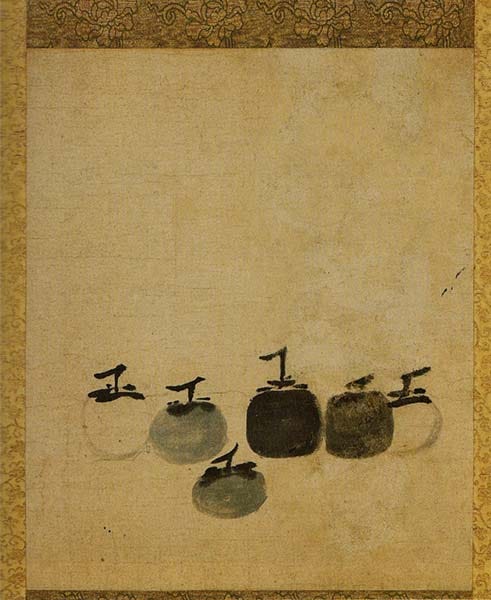

The painting of six persimmons by the Chinese artist Muqi is something you will find often reproduced in books about Zen Buddhism. Some people (mainly in Japan) feel the painting to be a perfect embodiment of the Zen aesthetic, specifically of the notion of wabi-sabi.

Occasioned by the Heart of Zen exhibition at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, where the painting is on rare display, I decided to re-read Leonard Koren’s two wonderful little books, Wabi-Sabi: For Artists, Poets, and Philosophers and Wabi Sabi: Further Thoughts. The first book is one I have read four or five times since it first came out in 1994. I had myself just arrived in Japan a few years earlier.

The closest English word to wabi-sabi is probably rustic, Koren explains.

I agree that “rustic” is not a bad match, since rustic evokes the simplicity and unadorned quality of wabi-sabi. I’ve also heard wabi-sabi described in English as “an acceptance of beauty in something that is transient and imperfect.”

Something I love about Koren’s approach is the way he looks at one concept by contrasting it to another.

So here he looks at Wabi-Sabi vis-a-vis that of modernism.

Modernism versus Wabi Sabi

logic based intuition based

absolute relative

modular one of a kind

mass-produced variable, hand-made

future oriented present (no progress)

control nature adapt to nature, bend to nature

square circle

slick rough

unambiguous dark and dim

His second volume Further Thoughts is better still since he does a deep dive into the words themselves.

The first thing he points out is that despite the fact that both wabi and sabi are ancient terms, they have not been used as a set phrase until very recent days.

わび・さび(侘《び》・寂《び》

“Sabi” 寂《び》dates back to the 8th century Manyoshu poetry anthology. The word itself is borrowed from Tang poetry and means lonely and desolate. A feeling of sadness but also an appreciation of imperfection, incompleteness, muted etc.

This is distinguished from the feeling of nono-no-aware sadness —or heightened awareness— about human fragility and ephemerality.

Sabi also means to rust. Or to be rusted.

Next is Wabi 侘 which is a word from the tea ceremony.

侘茶 Wabi-cha signifies a style of tea ceremony that was developed by sen-no-rikyu. I have not really heard the term “wabi” too much (if ever) outside the tearoom. Wabi tea is rustic. Beginning with the almost empty tea room where anything extraneous has been removed. Prized objects are often humble and taken from non-tea contexts; broken things are repaired—and the overall atmosphere is the wonderful simplicity of a clean thatched hut with un plastered walls.

Perhaps counter-intuitively, but sometimes within the desolate and pared-down atmosphere of wabi, one can attain the sublime and other-worldly—called yugen.

This was my experience standing in front of Persimmons this week. After wanting to see the picture for two decades and never managing to make it to Kyoto on the one day it is on display every year at Daitokuji Temple, I could not believe my eyes when I read in the New York Times that it had crossed the ocean and was on diplay in San Francisco.

Humble, rustic and a celebration of the blessings of the everyday, I suddenly thought of one of my favorite poems in the world—which is a great expression of sabi (I think?)

Tao Yuanming's poem, Plucking chrysanthemums by the eastern fence:

採菊東籬下

The poem sums up perfectly the serenity achieved by a life of cultivation –at the end of the hero's journey.

飲酒詩 陶淵明

結盧在人境 而無車馬喧

問君何能爾 心遠地自偏

採菊東籬下 悠然見南山

山氣日夕佳 飛鳥相與還

此還有真意 欲辨已忘言

Drinking Wine (#5)–Tao Yuanming

I’ve built my house where others dwell

And yet there is no clamor of carriages and horses

You ask me how this is possible– (And so I say):

When the heart is far, one is transported

I pluck chrysanthemums under the eastern fence

And serenely I gaze at the southern mountains

At dusk, the mountain air is good

Flocks of flying birds are returning home

In this, there is a great truth

But wanting to explain it, I forget the words

(my trans)

It is in nature where we can find truth. To be untrammeled and easily satisfied. It is the great beauty of our everyday world, if we only stop to notice it. Like those six persimmons. Will be writing about the picture Monday in a short essay at 3QD about driving nearly 800 miles this week to spend an hour looking at the persimmon painting in San Francisco.

Other “untranslatable” words: Nogomi and Yugen and Mono-no-aware

This one is a must, if you haven't read it yet--I loved this book so much-- it's not Kanazawa but close. https://www.kyotojournal.org/uncategorized/savoring-the-artisans-life-in-a-japanese-mountain-town/

Have you come across this https://japaneselit.net/