Waves of the Blue Sea: A Dance-Tune of the Tang Dynasty

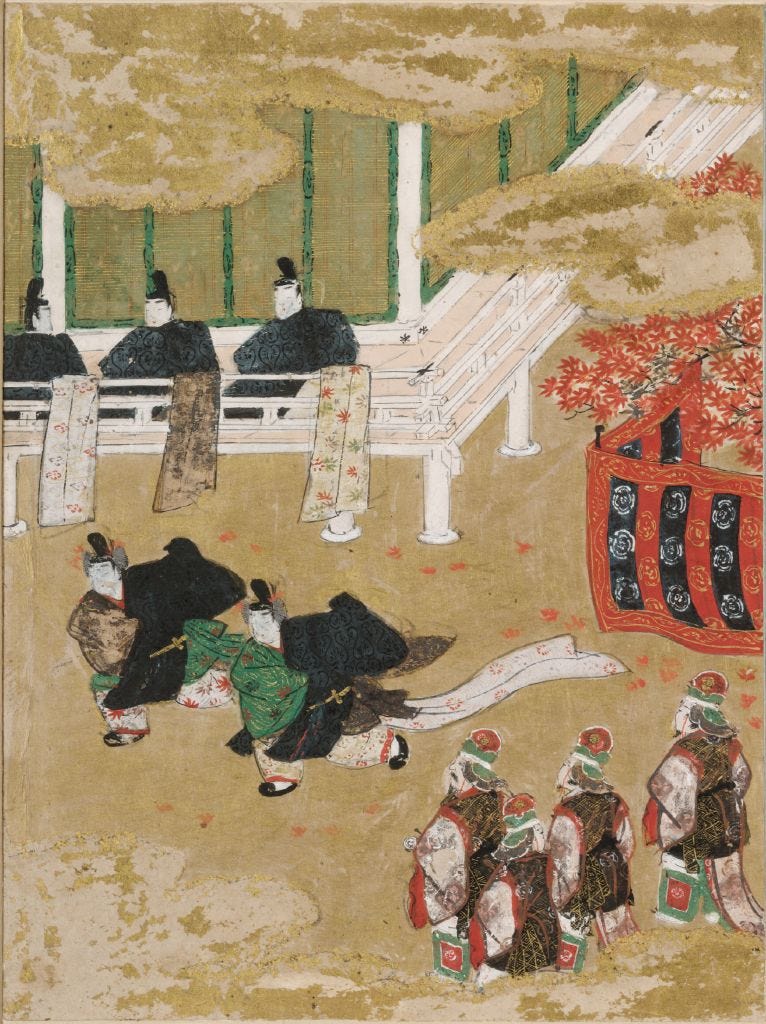

#7 A celebration under the red maple leaves—紅葉賀 / momiji no ga

As the Japanese imperial family watches from behind the curtains, Genji and To no Chujo perform a wondrous dance from China known as Waves of the Blue Sea 青海波.

Fluttering their sleeves to evoke rippling waters, everyone present watches in awe as:

The music swelled and the piece reached its climax in the clear light of the late-afternoon sun, the cast of Genji's features and his dancing gave the familiar steps an unearthly quality. His singing of the verse could have been the Lord Buddha's kalavinka voice in paradise.

Don't you wish you could have been there to see it? To hear it? To drink it in…?

The Blue Sea 青海 in the song’s title refers to Lake Qinghai in Qinghai Province, located in the romantic western reaches of China. Lake Qinghai is China’s largest lake and must have appeared like a vast inland ocean in the midst of drifting sands.

Waves of the Blue Sea entered the classical oeuvre during the Heian period, probably a century before Murasaki Shikibu was composing her novel. Called Gagaku (雅楽, lit. "elegant music"), Heian Court music is divided into three types: Saibara (native Shinto), Komagaku (Korean and Manchurian) and Togaku (Tang Music). Waves of the Blue Sea, borrowed from the Tang Court, is a classic Togaku piece.

What do you think of the music?

I once read an essay somewhere that compared Gagaku to whale song, with its haunting blend of flutes rising up from the deep, accompanied by the strumming of silk strings and the rumble of drums. Just by chance, I am currently reading a fascinating book called How to Talk to Whales, by Tom Mustill, and so have been listening to a lot of whale songs on Youtube, and I can kind of see where the comparison arose actually.

I assume the original Tang dynasty music was quite different from the Japanese —probably much more lively and sped up. This song, in particular, came to China by way of the Turkic kingdoms, even further to the west of Qinghai in Xinjiang, which is why the music is also known as Kokonor, from a Turkic word, which also means blue lake. It was during the Tang dynasty in China when things Turkic were wildly popular and many songs and dances from the western desert cities and kingdoms were imported into the Tang court as “exotica.”

While the Tang capital of Changan was the largest, most international city in the world of the time, the Second Capital of Loyang was no less impressive. Both cities were inhabited by traders, entertainers and religious teachers and students from places as far-flung as Syria, Oman, Iran, Khotan, Sogdiana, Turkestan, Tibet, India, Champa, Funan, Korea, and Japan, just to name a few. There were Mosques, Jewish, Manichean and Zoroastrian temples, Nestorian churches, as well as Buddhist monasteries of all sects, some of which were great centers of scholarship. Most surprising (considering the inward turn China would take in the coming centuries) was how stunningly exotic and open the city was.

It was a city where ladies adorned their cheeks with crimson laq from Vietnam and anointed their bodies with perfumed oils of Cambodia; where aristocrats kept falcons from Korea, parrots from the jungles of Java and lapdogs from Samarkand. Sleeping in Turkish felt tents was the latest fashion as were the dance moves from Sogdiana. And, the music. The capital saw glorious performances by dancers from Central Asia and India showing dances of such beauty that the famed Tang poets of the time composed poem after poem about them. Grape wine had also come into fashion and was served in glass ewers from Persia. There were lychees from Canton and those oh-so famous peaches of Samarkand.

Of course now the great civilizations of the desert are long gone. Covered in sand, if it weren't for the murals of Dunhuang and the Tang chronicles, we would hardly even know of their existence. Not only the civilizations, but the languages too are mostly dead. Kuchean, Sogdian, Khotanese, they are nothing but echoes in the desert. In China, too, we only have the written record.

And so it is wonderful that so many of the Central Asian songs imported from the Tang court are still performed today in Japan. Just like a perfectly preserved roman glass goblet that you can still use to drink wine, the Japanese Imperial Household has preserved and continues to perform this music!

Notes:

I think in this version, you can maybe hear something of the central Asian roots of the music.

Here is a short article on the roots of the Waves of the Blue Sea: 'The Waves of Kokonor': A Dance-Tune of the T'ang Dynasty

Rembrandt Wolpert, Allan Marett, Jonathan Condit and Laurence Picken

Asian Music

Vol. 5, No. 1, Chinese Music Issue (1973), pp. 3-9

The Waves of the Blue Sea 青海波 or Qinghai Wave pattern is also preserved as a famous pattern or motif in Japanese design. You see it everywhere, even in my sashiko embroidery! Below in rainbows…

Thank you so much for this! I am getting so much out of your essays, these are all things i don’t know about the culture of the period and they give so much depth to reading Genji. Really enjoying these essays, please keep going!

This is extraordinary performance! And the music! Thank you so much for posting this. I feel the music resonating in my very bones. Your description of life in Loyang brings its sophistication to life.