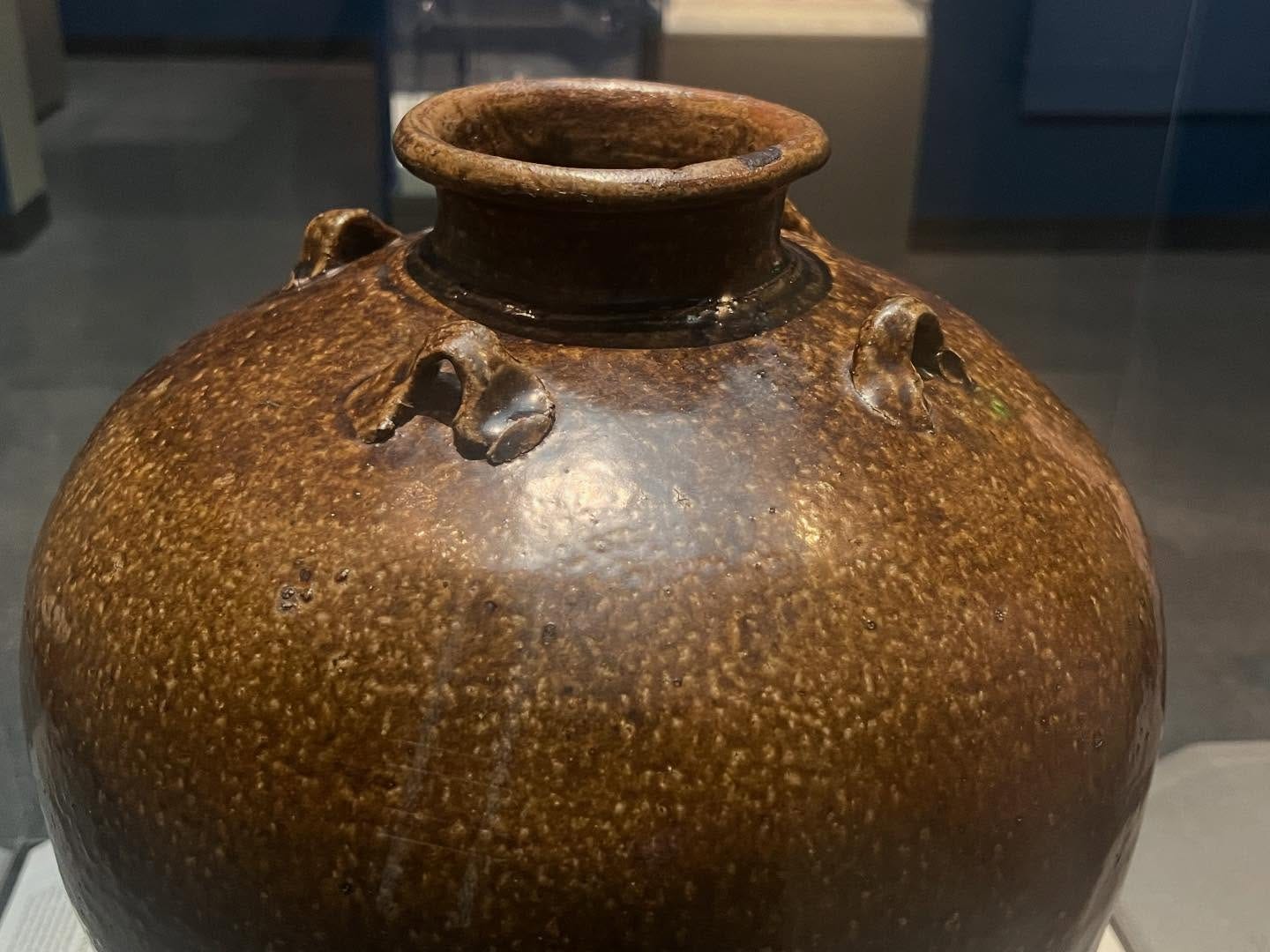

Southern Song or Yuan dynasty, 1260–1368 Tea-leaf storage jar, named Chigusa, mid 13th-mid 14th century Stoneware with iron glaze h. 41.6 cm., diam. 36.6 cm. (16 3/8 x 14 7/16 in.) The Freer and Sackler Galleries, purchase

Many people might disagree, but I consider the jar above to be the most important—no, the most ravishingly gorgeous— work of Japanese art held in the United States.

I love imagining it being born, a shape so ancient it was known by hands and hearts to the potters of a Southern Chinese kiln seven hundred years ago. Built up in coils and coils of clay, rough with sand and tiny stones, it is covered in an iron oxide glaze, dark caramel except for the bottom which is left unadorned. Compared to exquisite imperial porcelain, the jar was no big deal. Just a large size vessel for storing things like rice or vinegar.

But then it arrived in Japan, and no big deal became a very big deal. It is unclear exactly when it arrived on Japanese shores, but washing ashore it was a revelation. And those clever tea masters in Kyoto realized that a jar like this—something from faraway China— was the perfect vessel for storing tea leaves.

And so it was.

Changing hands for greater and greater fortunes, the jar acquired its name . Possessed by shoguns and tea masters down through history, the Chigusa took on an heirloom status. Like a movie star dressed in indigo silk and antique brocade, the jar was compared to the colors of flowers, wildly blooming and tangled up in autumn fields, and kept in nested boxes of cedar and lacquered paulownia wood. The Chigusa was like a thousand grasses or a thousand thoughts or a thousand poems or a thousand ways of falling in love.

Centuries later, it found its way to America, where it was purchased by the Smithsonian for $650,000, a bargain in 2009 since it came with those lacquered boxes and precious textiles and a thousand thoughts and a thousand poems. What a rags to riches story, whence a humble object becomes an object of desire, treasure of nations!

But now it sits behind glass, instead of filled with tea. Sometimes displayed in ceremonial silk cords, no longer announcing the time when summer makes way for winter in the tearoom. Still, it’s the greatest work of Japanese art in America, I said. He coughed, muttering something about Korin and his irises.

He later conceded that it did have that great journey, such a world traveler. Without that story though, he said, it is nothing but a lump of clay. Just like us, I said. Stories molded in clay.

I just arrived at my second residency at VCCA in Virginia, and before heading down from DC, my husband sweetly double parked in front of the Freer gallery at the Smithsonian and waited while I dashed in to see the Chigusa—something I have long wanted to do!

In Japan, even now in spring, tea masters and teachers will send their jars to the tea plantations where they buy tea and wait for the jar’s return months later, packed with tea leaves. Then in late autumn, after the tea leaves have mellowed from more fermentation, the tea jars are placed in the alcove on display for the kuchikiri no-chaji 口切りの茶事.

This marks the time when the portable brazier used in summer is put away and the season of “ro” or the sunken hearth is begun. It is also considered to be the tea ceremony’s New Year.

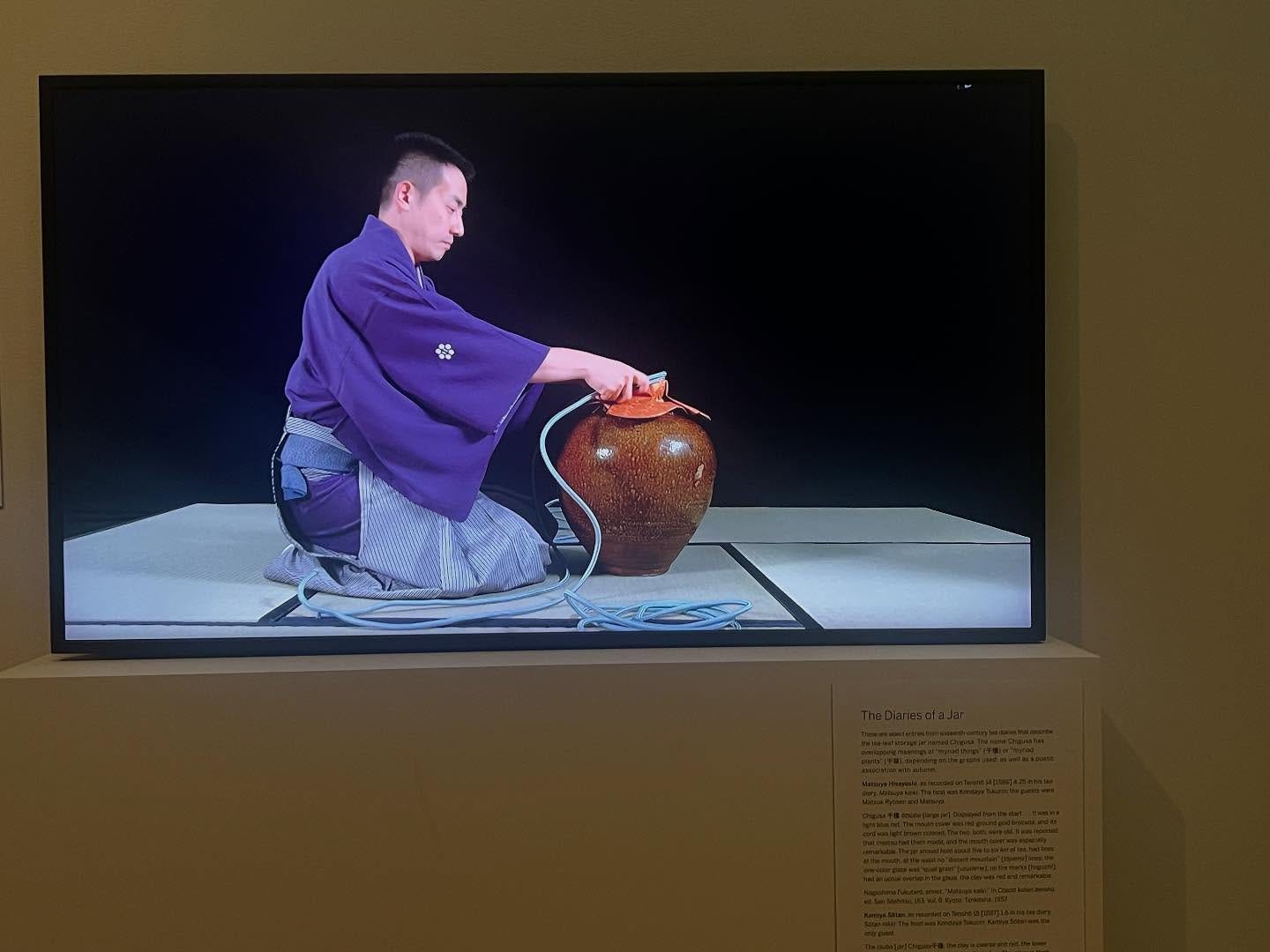

The museum had a video showing the jar being dressed in its ceremonial silk cords.

秋の野に乱れてさける花の色の ちぐさに物を思ふころかな

++

VCCA is beautiful! I found this article from 1988 about another writer who had my studio in this incredible renovated French Normandy-style barn: the Nida Tomlin Watts Studio. It’s a lovely essay.

Like the Vermont residency at VSC, this one has a bedroom in the main house and then a studio, which also has a bed… lots of spots to read! Outside is thrumming with HUGE wasps and bumble bees and cicadas… a painter told me there are fireflies at night.

Compelling and lively description of the star status of the Chigusa! Such a different world. I once read a quote (don't recall where from - may even have been from Isaiah) that "the potter understands". That definition, distinguishing ceramics from all other arts, really impresses me and seems to fill your own revelation with the experience of the Chigusa. And then on to Virginia; so different from So Cal. Hopefully you see many fireflies, their dances inspiring the images of your poems with the appreciation that you live so effortlessly.

Beautiful, both the chigusa & the residency! Reminds me of tea ceremony seminars in remote monasteries, our rooms were similarly spartan, although of course we hardly spent any (waking) time in them.