1.

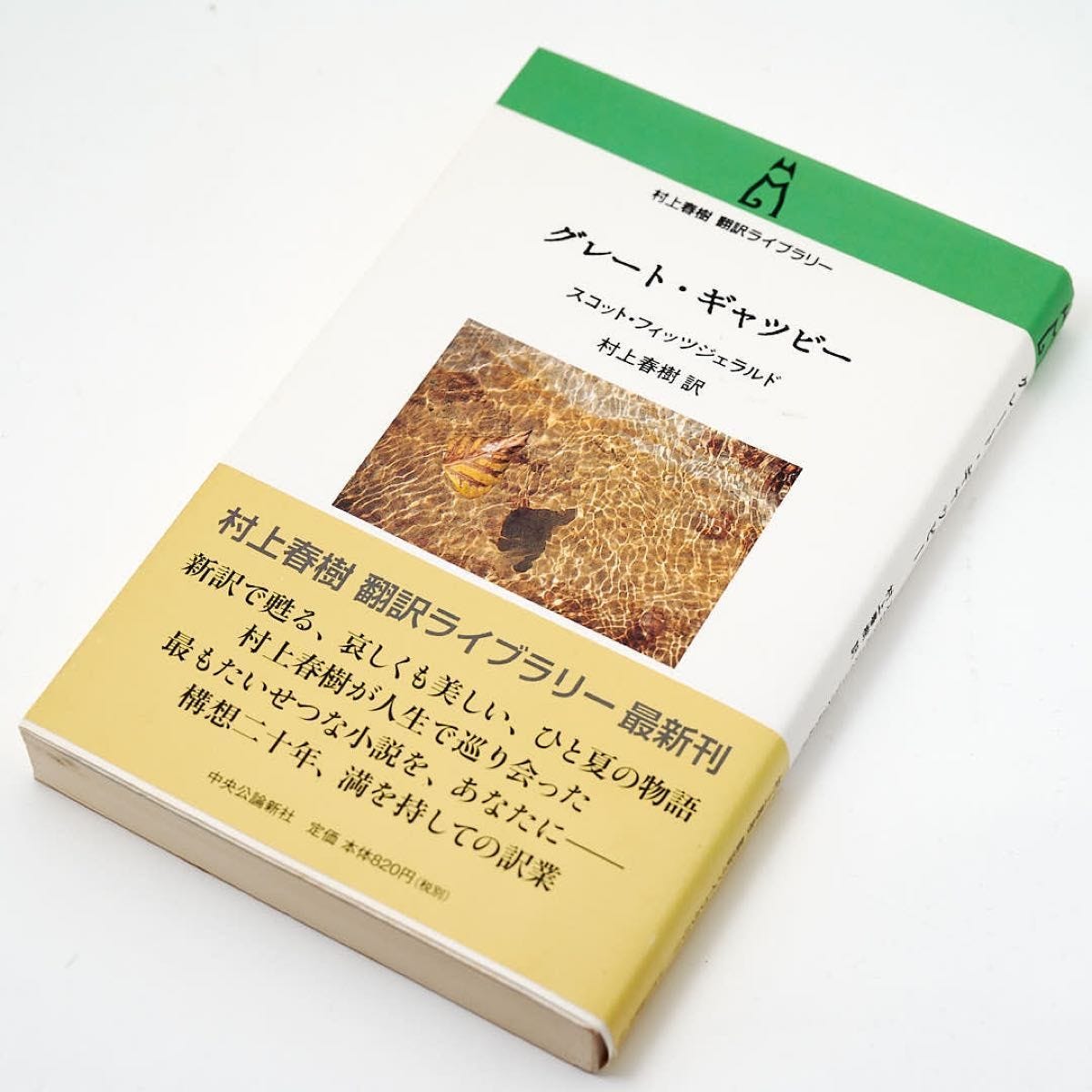

By the time Haruki Murakami was in is thirties, he’d already made an oath to translate The Great Gatsby into Japanese by the time he was sixty. This was a promise so solemn that he placed his Japanese copy of the novel on the kamidana in his home, the shelf usually referred to honor the Shinto gods.

Translation is, after all, the most intimate kind of reading and also the most rigorous form of textual analysis. I say that without any qualification—because I think it is true. In the introduction to his translation, Murakami writes of being deeply impressed when he learned that Hunter S. Thompson typed out the entirety of The Great Gatsby, end to end, before he’d ever written a book of his own, just to see what it felt like.

In my essay in the Millions about writers workshops, I mentioned how I was given exactly this same advice when I started playing around with the idea of becoming a novelist—not once but twice!

“Whatever you do, don’t get an MFA”

And

“Don’t show anyone your work, other than a few trusted friends”

And

“If you really want to learn how to write, copy out a favorite book by hand.”

2.

Translation is like that: a deep read. More, it is an internalization of the text… breathing in the original version and eventually (after being fully digested) exhaling the translation, but as others have written time and time again, every translation is a failure of some kind, something is inevitably lost in translation, as every translation in is somehow necessarily imperfect. Knowing this, for his Gatsby translation, Murakami decided to focus musicality. That is, he decided when two issues are in conflict, for example, meaning versus sound, he always chose the latter.

Often translators have to make these kinds of global decisions. When I worked on Takamura Kotaro’s Chieko Poems, I made a very conscious decision, knowing that something would have to give, to place my emphasis on the images of his poems. As a sculptor, Kotaro really works in these unforgettable images. Like that if a woman on her deathbed biting into a lemon, or the ice on the River Jordan. He also has a unique tone and voice that is not the same poem to poem. So I tried to convey that as best as I could. Maybe sound or sentence structure had to give, though..?

In addition to the musicality of the sentences, Murakami also wanted to created a work that wasn’t frozen in time. He writes that translations have their expiration dates. And I do agree that reading a Victorian rendition of the Tale of Genji is startling. It might not really work as well today as the newer, updated translations. It is interesting to think that while novels do not usually have “best by” dates, translations do go out of style.

3.

So how do you think Murakami translated the phrase made famous by Fitzgerald: “old sport?”

Yep, he left it in English. He writes how lucky he was that most Japanese could parse that back then when his translation came out. Hilariously he remarks how sad for all the English language translators of Soseki who couldn’t just leave Kokoro in the Japanese. Of course, it was left as is in the title of the English translation of Soseki’s novel, but had to be translated within the pages.

4.

So if you were going to pick one book inscribe onto the pages of your heart and make truly your own, what would it be?

For Murukami it was, The Brother’s Karamazov, Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye, and of course, Gatsby.

Mine would be the Brothers Karamazov, the Quixote, and the Kokinshu poetry anthology. The last one is the only would I would choose to try and translate, but if I could set a real goal, I would like to translate the poetry of Du Fu or Li Qingzhao. Someday…..

5.

Along with Haruki Murasaki, Soseki Natsume was known for his essays about English literature, as Ogai Mori was for his translations of Hans Christen Andersen and Goethe. Translators can make wonderful novelists (and I hope to become one someday myself!)

I am now reading—and loving Irena Rey by Jennifer Croft. I have read (maybe in the Guardian?) that she is our best living translator. And she is a stunning novelist. I love Irena—and highly recommend it. Am also making my way through Caledonian Road by Andrew O’Hagan (compared to Dickens). I hope both are long-listed for the Booker Prize (three more days till they announce!)

++

Murakami’s essay was one of the many interesting essays in In Translation: Translators on Their Work and What It Means by Esther Allen, Susan Bernofsky

The "dated" quality of translations is interesting to me. I have several translations of Sappho's poetry. There is less obvious differences in the translations that are attributable to the time in which they were translated. The original texts are mostly fragments (only one or two complete poems), however, and I think this contributes to the situation -- less of the original available, more to discern but less to fuss over. Does that make sense? I really applaud how you chose the emphasis on image for the Chieko poems.

I mean, can the man actually write ordinary Japanese?