Oracle Bones and Writing in the Time of the Gods神代文字

1.

What if before the adoption of Chinese characters, the Japanese had their own script?

When I first arrived in Japan, I was surprised to discover that the country did not have a writing system of its own until it borrowed one from China. And that this had not happened until the 5th century of the common era, when Chinese first found its way to Japan inscribed on mirrors and other gifts from Korea. This was then followed by books, like the Analects of Confucius. After these initial introductions, it took centuries before the Japanese were able to adapt and use the Chinese characters to write in their own language.

Was it possible that this land seemingly soaked in ancient traditions was, in fact, something of a late cultural bloomer?

Given my own initial surprise, I suppose it is not unexpected that in later times, Japanese scholars would invent theories about a native script that existed in Japan before the arrival of Chinese. Japan couldn’t have been that backward, revisionists argued. Surely, the Japanese had some form of writing before it borrowed Chinese characters, Edo-period nativist thinkers insisted.

They even came up with a name for this long-lost script: jindai moji or kami-yo moji 神代文字--meaning “age of the gods script.”

And over the centuries many contenders were trotted out as possible gods age script.

2.

The Japanese word kami 神 –or “gods”--cannot be mapped onto the English term for a monotheistic God-- nor even to that of the polytheistic gods of the Hindu or ancient Greek pantheons. Kami has an animistic origin, referring to nature spirits, such as those found in mountains, old trees or lightening, for example. Kami can also be anthropomorphic deities tied to Japan’s foundation myth, like Izanagi and Izanami; as well as to certain human beings, such as kings and emperors or dead ancestors.

Before the arrival of Buddhism to Japan, the ancient Japanese worshipped “kami.”

So, the “age of kami” refers to this period of time before Buddhism and the Chinese language. The term also refers to the time before Japan’s first emperor, Emperor Jimmu, who was himself a descendent of an important kami.

Jindai moji is the supposed script used before Buddhism and the arrival of the Chinese language. It was also the supposed script used before the first emperor heralded in the “age of human beings.”

Jindai moji was the script used to communicate with kami. It was also the supposed language of the kami themselves.

3.

It was the ancient desire to communicate with kami that generated one of the main arguments that Japan must have had a native writing system before the importation of Chinese. The fact that the Japanese were trying to communicate with the gods is based on a brief description found in Japan’s second oldest chronicle, the Nihon Shoki, which was completed in 720 (again, a relatively late date in history). This description was about the Urabe family monopoly on “Turtle Fortune-Telling” (亀卜, Kameura, "turtle fortunetelling”).

Turtle fortunetelling refers to plastromancy – a form of divination in which questions were posed to various kami using turtle plastrons (and deer scapula). For those who don’t know, turtle fortune is an elaborate process which is another import from China. The ritual began with the cleaning of the shell, after which a symbol was carved dividing the space into five zones. After this, the diviner would engage in purification and prayers lasting days. When everything was deemed auspicious to begin, the shell would be heated using a burning poker made from a bird cherry tree. The heat was applied until multiple hairline cracks formed, which the diviner would then “read”— not unlike reading the future in tea leaves.

One of the reasons that later revisionist historians in Japan posited there must have been a native script predating Chinese characters was that they figured it was necessary for carrying out the above divination rituals. Plastomancy was imported from China centuries before the language arrived on Japanese shores—and in China, words in the form of Chinese characters were carved onto the shells and scapula.

Evidence of Japan’s early adoption of plastomancy comes from the Chinese records themselves. The 3rd century Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms describes the practice in its section about the Kingdom of Yamato (Japan). Evidence also comes in the form of archaeological artifacts. According to Stephan N Kory in his fascinating paper From Deer Bones to Turtle Shells: The State Ritualization of Pyro-Plastromancy during the Nara-Heian Transition, Japanese archaeologists have uncovered more than a hundred and fifty divined bones from over thirty sites spanning time from 100 BCE to 800CE. Kory’s fascinating paper charts the way deer scapula were later passed over in favor of tortoise shells.

4.

Turning back the clock 2,000 years before Japan’s earliest experimentation with divination, Chinese diviners, on behalf of kings and aristocrats, were posing questions like this to the gods:

Will it rain?

Is it a good time to plant rice?

Will the king’s tooth stop hurting?

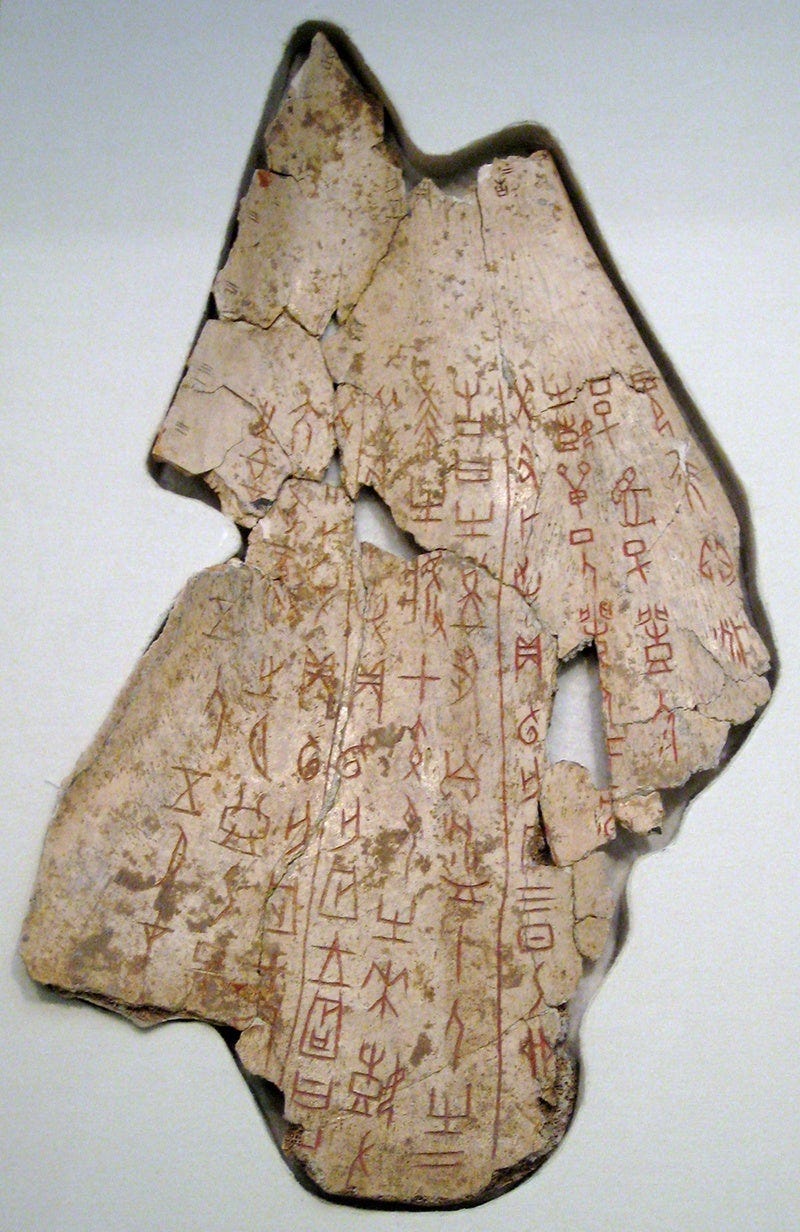

After posing the questions in prayer and incantation, the shell —or bone— was heated to create hairline cracks on the surface. The diviner would then read the future by analyzing these cracks. After the answer was gleaned, the diviner would then carved the question directly onto bone or shell relative to the relevant cracks.

So, in China, writing was definitely involved in the divination ritual.

And as it happens, it is upon these artifacts where we find the oldest extant version of Chinese writing. This does not mean we might not someday older writing still. But the script found on these bone and shell fragments is the oldest form of Chinese writing we know of, so far. Known as the “oracle bone” script --it was used to communicate with deities in the divination rituals. The Japanese linguist Shirakawa Shizuka (whom I wrote about previously in these pages here) spent a lifetime uncovering how the archaic characters were themselves born out of this human-deity communication nexus.

5.

Because of the overwhelming cultural supremacy of China for a thousand years of Japanese history, it is natural that there would be pushback. And the god age script theories were part of that. This began in Japan in the 15th century, but really picked up during the Edo period as part of the Kokugaku movement, which was focused on resisting the inherited Chinese cultural tradition in favor of uncovering a purely Japanese tradition.

Kokugaku was an anti-Buddhist, anti-Confucian school of nativist thought. One of the loudest advocates of Japanese racial and cultural supremacy of the time was Motoori Norinaga (born in 1701). One of his interesting contributions to the discussion of the god’s script was that, in his opinion, Japan’s spiritual purity could be seen in its NOT having a written script.

His basic thinking was that the spirit of the Japanese has always been stored in its oral history, in the form of songs and poems. From ancient times, he argued, the Japanese have preferenced sounds, songs, chanting and incantations. This is captured by kotodama, a word much touted by kokugaku thinkers. Kotodama (word/spirit) is the mystical power of words and names. It is an ancient belief in Japan that words can magically affect the world. In the oldest poetry collection, the 8th century Manyoshu, there is a verse that reads, Yamato is a country that is blessed by kotodama. 言霊の幸ふ国~~.

To be —cont—

Notes:

Oracle Bones:

I was surprised to learn in this short article in JSTOR daily by Jacob Mikanowski how wide-spread this kind of divination was in history.

A scapula warned Attila about his defeat at the battle of Châlons, while Genghis Khan used scorched sheep bones as a check on the reports of his astrologers. One of the most intriguing uses of scapulimancy comes from the Naskapi, an Algonquian-speaking tribe who lived in the tundra lands of Canada’s Labrador Peninsula. The pattern of cracks in a caribou shoulder blade contained their prophecies. The most important question was always this: What direction should the hunters go in search of game?

Why scapula bones? Why tortoise shells? And why the significance of the cracks after applying heat? Why did multiple cultures decide to go this route? Mikanowski writes that, “for the Shang, the scapula bone worked like a radio, tuning in to the spirit world.”

Here is one last tidbit about the bones: In modern China, farmers began to uncover shells and bones with strange markings in their fields, in Anyang. Having no notion that the marks on the fragments were actually an archaic form of Chinese writing, they sold them to apothecary shops, where they branded as “dragon bones.” Ground up as medicine, dragon bones were thought to be a good cure for stomach issues and malaria. It would take a sick scholar at the turn of the twentieth century (1899) to figure out that his medicine was an ancient Shang dynasty artifact and that those markings were in fact an ancient form of Chinese characters. Imagine how many wondrous pieces of ancient writing ended up in people’s stomaches?

It was an American collector—a missionary in China at the turn of the century Frank H. Chalfant, who coined the term oracle bones. The name stuck and the term was then calqued back into Chinese --as jiǎgǔ 甲骨.

Japan:

While turtle shells became more popular during the Nara period (8th century), when everything Chinese became the height of fashion, in earlier times, other animals were used including (according to Kory) seventy-five deer bones, twenty-one wild boar bones, forty-six dolphin bones, and four loggerhead turtle plastrons.

Yet another element of the insecurity that drives 日本人論. A good read, Leanne. Thank you.

So interesting Leanne, thank you.

There’s so much cultural history in this world that one could learn, and the farther back you go, it’s so far flung and so unique and so fractured and distantly related that maybe an important way to keep growing is to find and follow learned people in fields that you know nothing about. I know nothing about Japanese prehistory, but I enjoy learning from you here.

And I feel naive to divulge that you’ve just taught me the meaning of the title of Peter Hessler’s book Oracle Bones. Thanks! His previous book River Town, about his time in the Peace Corps in rural China, was revelatory to me.

I’m being presumptuous now: does Kokugaku the anti-Buddhist, anti-Confucian nativist bring to mind any … contemporary American ways of thinking?