Taiwan Travelogue: A Novel by Shuang-zi Yang

National Book Award Finalist in Translation --Translation by Lin King

Ah, the Southern Country! Ah, the Island! Ah, Taiwan!

1.

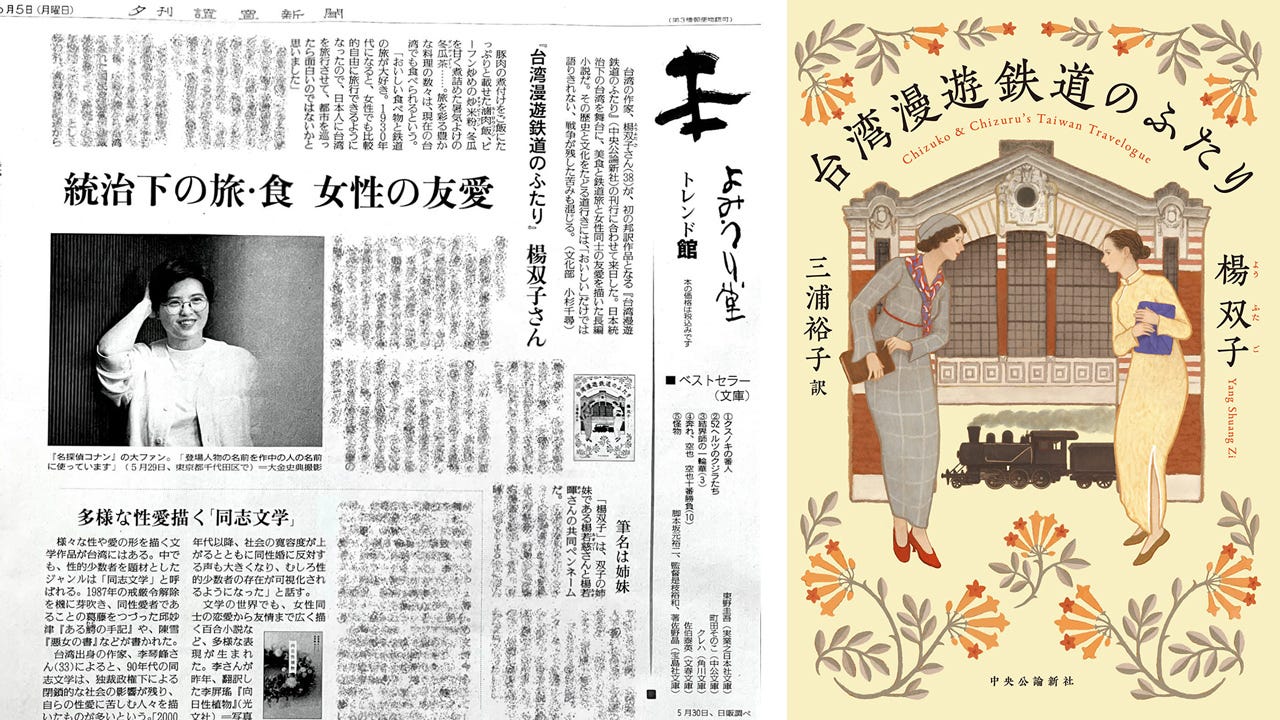

Tonight the winners of the National Book Award will be announced. In translation, one of the finalists is already a real winner! An English translation of a Mandarin novel that is written disguised as a translation of a rediscovered text from a Japanese writer. In the original Chinese language version, author Yang Shuanzi playfully had herself listed as “translator” on the book cover. She wanted readers to really get into the idea that they were reading a Chinese translation of a text originally written in Japanese.

Readers complained!

English translator Lin King wanted to preserve some of the nesting-doll narrative quality of the original text in the English version of the story about a Japanese female author named Aoyama Chizuko, who travels to Taiwan during the colonial period, falling in love with her female guide and interpreter known in japanese as O-Chizuru.

As you can see, it is a play on the old trope of colonial love affair between a European man and native woman. That said, while the genders and races have been switched up, this story is still very much about power dynamics and colonialism.

2.

Japan’s rule of Taiwan began in 1895. And as the translator Lin King notes in an interview in Electric Literature

This novel is set in the 1920s-30s, when Taiwan was part of the Japanese empire. A lot of English-language readers might not know this, but Taiwan was governed by Japan for 50 years, from 1895 to 1945. During this period of time, the idea of Taiwanese identity had yet to be fully formed—it wasn’t a nation, but a place where indigenous Taiwanese peoples and migrants from China had settled and called it home. The idea of Taiwan as a nation wasn’t there. When Japan took over, people in Taiwan were told they were now children of the Japanese emperor. This included my grandparents, who were educated in Japanese as kids. In World War II, they fought in the Japanese army.

I spent a very happy time in Kaohsiung about twenty years ago.

My Japanese husband and I called it Takao 高雄.

Takao is the Japanese pronunciation of 高雄, while Kaoshiung is a Chinese pronunciation for the same characters.

Even when I was there, so many older people spoke Japanese fluently. And Kaoshiung reminded me a lot of Kawasaki. While the south felt tropical and so different from Honshu at least, still it felt very familiar and comfortable coming from Japan—and I think it is safe to say that the Japanese influence is significant.

As King writes that

There’s an idea that Taiwan’s current difference in identity from Mainland China in large part begins with this seismic shift we had during the 50 years under Japanese rule. Taiwanese society is largely made up of Minnan or Hakka people who migrated from Mainland China, and some people use this to argue that Taiwan remains culturally Chinese, but one irrefutable wedge is the half-century under Japan. I think if people in the West were to know more about this, they’d gain a better idea of at least one reason why Taiwan asserts itself as distinct in identity. I don’t know if Shuang-Zi intended it to be political, but I think it’s inevitable to read Taiwan Travelogue through a geopolitical lens.

3.

That is one fascinating part of the novel: the way it highlights this little understood period of time in Taiwan. But another wonderfully done aspect of King’s translation is how she handles language.

The above city name is just one example.

If 高雄 is Takao in Japanese and Kaohshiung in Chinese and in English, what do you do if the narrator of the novel is thinking and speaking from a Japanese female perspective in the 1930s. Well, you call the city Takao and put a map in the front of the book. And the same with all the Chinese romanization—what to do? Even now, Taiwan keeps to the old Wades-Giles system, while the rest of the world has shifted to Mainland China’s pinyin system for rendering Chinese. For example, Kaohshiung is the old Wades-Giles version of the Chinese characters for the city. In Pinyin, it is Gāoxióng.

So, what is a translator to do? Takao? Gaoxiong? Kaohshiung?

The translator’s name in the novel is Wang Chianhe—but that is rendered in Japanese as O Chizuru—and so I was surprised that the english translator chooses the Japanese spelling—and yet that makes sense since the narrator is thinking in Japanese!

The novel demanded that the translator make countless such decisions, perhaps most challenging of all was rendering japan’s polite language. Because the characters were depicted under a colonial backdrop, the Japan-born author was considered highest in status, while her guide and translator O-Chizuru was much lower being of Chinese descent (her ancestors came to Taiwan from southern China during the Qing dynasty). In the pecking order, far above people of Chinese descent were the Taiwan “island-born” Japanese people, known even today as “wansei” 湾生.

The bottom rung of society were the indigenous peoples, known as banjin (not such a nice term)

I am telling you all that so you can imagine the somersaults required to depict how O-Chizuru must have constantly been speaking in honorifics to her Japanese-born author. This polite language does not exist in English or Chinese and so the author made great use of a Japanese translation of the Chinese novel to gain a good footing for how to handle it and then she tried to somehow reflect this in her English version in the way she addressed the author or had Chizuru speak more formally.

4.

All of these linguistics somersaults were handled using translator’s notes—giving the novel a wonderful “meta” edge to its telling. Because the Chinese version was masquerading as a translation of an original Japanese text, the author Yang Shuanzi included footnotes, so for this english version of the novel, the translator was happy to run with that. I was thinking how well it works too.

These days, translations aim for a seamless quality. They are suppose to allow readers to feel as if they are reading the original so that readers never “fall out of the story.” This idea of immersing readers in story is very much prized in writing workshops, and I think it comes from TV: this idea of being immersive in ‘story.”

But I always think that novels can do so much more than TV.

In one of my online book groups, someone said

I don't read translated fiction, as I believe it adds in another 'voice' - that of the translator - and so I imagine it is not the 'authentic' prose that the author intended. For me fiction is not so much what you say, as how you say it - I am more bothered about the quality of the prose, than the plot. Therefore the choice of words is crucial. I want that choice to be that of the author - not the translator.

It’s true that a translation will always be a treachery on some level—and yet what if all translations came with extensive footnotes explaining the decisions made by translators step by step? For those who just want the story, they could ignore—but for those who really wanted to have more, the doors would be open to a very different kind of experience. I loved how intellectually stimulating it was to read this translation.

5.

In case I have not made a good enough case for how fun and interesting this novel is, I wanted to end by mentioning that while I admired the book for being a tour de force in translation, I fell in love with it for its writing about food.

Anyone who has spent time on the beautiful island of Taiwan will know it has some amazing things to eat!! And this novel describes many of them. Aoyama-san is a self-described glutton… she calls it her monster in her stomach and all she thinks about is eating… this is a stand-in for the desire she feels for herTaiwanese translator and guide—but wow can she eat a lot!!

For someone like me who is endlessly dieting and if I am honest, I am usually hungry too…. it was delectable torture to read the book…. it goes on and on from bamboo-wrapped rice dumplings, meatballs, taro balls, melon seeds, salty cakes, and an impressively wide variety of noodles and desserts to curry rice and sukiyaki…. it made me so HUNGRY!!!!!

++

By the time you read this, the announcements will have been made… while I did not read any of the other translations, I did read all the finalists in fiction. I loved all five… in order I would choose:

Martyr by Kaveh Akbar

My Friends by Hisham Matar

All Fours by Miranda July

James by Percival Everett

Story Collection by Pemi Aguda

All five were fantastic!!

And it won! How cool is that!

A timely read to land in my mailbox! (I hope you saw the email I sent you the other day). I, too, am struggling with translating Taiwanese Chinese. This book sounds fascinating!

Even the idea of talking about a 'Taiwanese identity' is incredibly fraught, if ethnicity is the only criteria. Seems to me a case for almost anything can be made depending on how far back you go.

PS. I've just read a brilliant literary translation mystery I highly recommend, about a Taiwanese literary translator, by Jessie Tu, a Taiwanese-born Australian writer. It's called The Honeyeater, from Allen & Unwin