1.

It is the most famous dream in Chinese history.

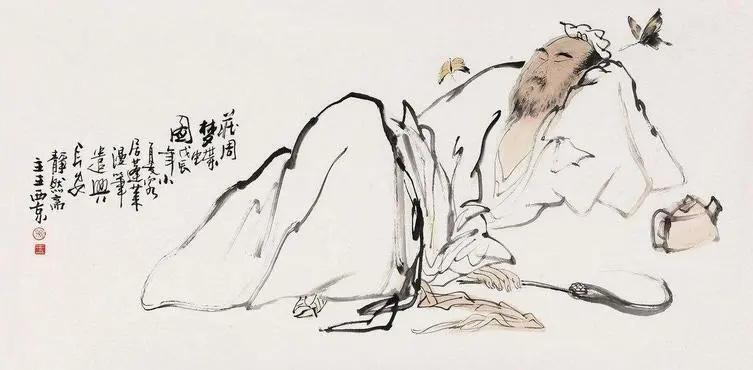

Long ago, during the Warring States Period (476–221 BC), a philosopher dreamt he was a butterfly. Fluttering and dancing in the air, he enjoyed being himself, doing just as he liked. He forgot that he was Zhuangzi. Suddenly he woke up and realized how he’d completely forgotten that he was Zhuangzi. But then he wonders, was I the man Zhuangzi dreaming I was a butterfly or am I a butterfly now dreaming that I am a man? Surely there must be some difference between the man and the butterfly. This is what is called “the transformation of things.”

Zhuangzi has been popular in Japan for a thousand years or more, so it was no surprise to see the Young Murasaki Shikibu using this text as a model for practicing her calligraphy in the drama two weeks ago. She had barely survived the plague— in her fever dreams seeing her beloved had come to look after her, not leaving her bedside all night. But was that really a dream? Maybe she had died of the plague and she was dreaming now in paradise, practicing her Chinese in the peaceful and tranquil quiet of home.

The border between fever dreams and our waking days can sometimes feel less clear. Hazy and surreal like dreaming you are a butterfly…

2.

But have you ever dreamed you were a creature before? Not only have I never in my life dreamt I was an animal, but I have never dreamt I was another person, other than myself. Sometimes I am a bit different—maybe a younger or more passive version than myself—but always in my dreams I am recognizable as being me.

If my dreams were a memoir, the story would have started very wonderfully. When I was young I had fabulous dreams. I’d write them down in a pretty little dream journal because they were that good. Even in my thirties they were often expansive and world-opening. But ever since I returned to California in 2011, my dreams have been tedious and totally unremarkable. Mainly showcasing how totally maladjusted I am to life here, all my dreams feel fueled by anxiety.

Thinking about this, I am reminded of Michael Pollan’s magnificent book How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence. In the book, Pollan very persuasively argues that as we grow older, our minds more and more fall into mental ruts as the ego takes over completely. This ego is a kind of short-hand for the “default mode network” in the brain. This is something that is not developed fully in children or other animals, but in humans, becomes very developed as we grow into adulthood. This is the “boss” of your brain and is very connected to our sense of self (and what we sometimes refer to as our ego). LSD seems to inhibit this part of the brain which allows different parts of the brain to become more active at the same time (hence the sense of a world infused with meaning; and the frequent experience of synesthesia). This means not much gets done in terms efficiency and producing, consuming…. But the drug, in generating a "high entropy” state can allow for some tremendous relief and insight as well.

Yes, it enables people to dream.

3.

Right now, I am preparing to take a class at Outlier Linguistics in Classical Chinese and just finished a bit of self-study.

Has anyone heard of Outlier?

I was a bit worried about tackling Chinese, so wanted to dip my toes in the water with Bryan W. Van Norden’s Introduction to Classical Chinese Philosophy, a book I cannot recommend enough. First thing every morning, I begin with writing practice using worksheets designed to practice the characters used in the lesson’s text. After getting over my horror at characters written different than I am used to in Japanese, and worse, NEW characters, I finally slip into my old habit of quiet practice. Morning writing practice was a much loved part of my life for two decades in Japan and it is great to be back at it.

The text is witty and filled with nerd notes. Each lesson centers around a famous excerpt from classical philosophy from Confucius to Mencius. Working hard to finish, I was thrilled to see the last passage we would study would be—you guessed it!— Zhuangzi’s butterfly dream.

In a note about 物化 (wùhuà) Van Norden says that the butterfly dream is not a skeptical argument in the way made famous in Descartes’ dream, but rather it is a way of laying out what he means by the “transformation of things” 物化

In the Zhuanzi, hua 化 describes the continuous process of change of the natural world in which there are no precise boundaries between one state and another. There are no absolute distinctions in the transformation of the living into the dead, or a caterpillar into a butterfly. So in not clearly distinguishing between himself and a butterfly, Zhuangzi has a more accurate perception of the world.

We see this idea of 物化 (wùhuà) a lot in the traditional calendar when there are several times of year when one thing turns into another, like moles turning into quails.

4.

Like van Norden in his Chinese language textbook, Chinese historian Robert Ford Campany finishes his book The Chinese Dreamscape, 300 BCE-800 CE with Zhuangzi’s dream as well. Age and ego aside, it is difficult to overstate how influential Freud and Jung have been in framing our modern understanding of dreams as expressions of our anxieties, fixations and unconscious drives.

But what if people’s dreams were different in other times and places? Campany is right to begin his study of ancient dreams by emphasizing the real possibility that our dreams are not only informed by personal factors, such as age and gender but also our culture and language.

Challenged at a conference about the possibility of standing outside one’s own preconceived notions, Campany was asked, “Can such a book be translated into Chinese?” He says of this question, “The point, as I understood it, was either that my paper was too enmeshed in Western categories and terminology to even be translated intelligibly, or that if it were translated it would have lost its point”. Responding to such concerns, he presents his book as a record of the process of his trying to understand the ancient texts. These sources include Shang dynasty oracle bone records of divinations, dream manuals from recovered ancient bamboo and wood slips dating from the Qin Dynasty (221 to 206 BCE), liturgical instructions found in texts, such as The Liezi and The Zhuangzi; as well as anecdotes of successful dream-based predictions found in poetry and history compilations.

Campany’s approach brings to mind Evan Thompson’s 2014 volume Waking, Dreaming, Being: Self and Consciousness in Neuroscience, Meditation, and Philosophy, which aims to analyze dreaming through the lens of the Indian Yogic traditions. Similar to Campany, Thompson tries to uncover different understandings of the self through the lens of dreaming. Both Thompson and Campany, in doing a deep dive into these ancient textual traditions concerning dreams — specifically the Upanishads for Thompson and the rich record of ancient divination and other records from classical and medieval China for Campany—are resisting the view that dreams are meaningless hallucinations of the brain. In the Buddhist tradition, for example, lucid dreaming is considered a trainable skill essential to the aspirant’s progress as a meditational adept: Thomspon writes that “Dream yoga tries to show us how the waking world isn’t outside and separate from our minds; it’s brought forth and enacted through our imaginative perception of it”. And Campany similarly analyzes dream manuals utilized for Buddhist practitioners in China, showing the way certain symbols reflected the dreamer’s status on their path toward liberation.

And what does he find?

5.

In the texts he analyzes, dreams often come as an assault and excursion from an exogenous thing like a haunting. They can be more positive like the gift of a visitation. They often can come as codes and puzzles to be solved or as an spillover extenuation of awaking cultivation activity. In all these cases, dreams appear to come from beyond, rather than as relentlessly from within a person’s psyche—as ghosts and gifts or as bread crumbs leading the way to answers.

The ancient Chinese view of dreams, explains Campany, “presumes a self that is dividual, multipartite, and fissiparous.” This includes Daoist notions of multiple cloud-souls (魂) and white-souls 魄). A person, then, is a multitude of souls that are capable of wandering outside the dreamer’s body during sleep. In this way, the dreamer is seen, less the maker of the dream, as the passive subject, witness, or even victim of the dream. In the texts, he says, this is borne out with dreams describes as being “the caused by x”. For example rather than “the king dreamed, “ the construction will appear as “the king’s dream caused by x” (王 夢 不 隹 大甲) Dreams, then, are not things that happen when the self retreats from the world into an idiosyncratic solipsistic cocoon, but rather dreams are seen as relational and inter-subjective.

Returning, as he must, to the butterfly in Zhuangzi’s dream, he says that Zhuangzi would point out that dreams are not necessarily the only way we can experience the transformation of things—for we see it at work in death and birth, as well as the turning of the seasons —and the great goal for people is to fully accept this world of relentless change and transformation with grace and equanimity.

To Study: Bryan W. Van Norden’s Introduction to Classical Chinese Philosophy

Evan Thompson’s Waking, Dreaming, Being: Self and Consciousness in Neuroscience, Meditation, and Philosophy

Oh I love this way of thinking about dreams!

You amaze me. So much to ponder here!