In Arkady Martine’s 2019 debut novel A Memory called Empire, newly-appointed Ambassador Mahit Dzmare travels via jumpgate from her home planet at the edge of the Teixcalaani empire to the capital. Teixcalaan is like the sun around which all the other planets in the empire revolve. The city of cities, it is the center of the Teixcalaani universe.

Arriving in the capital, the new ambassador is immediately invited to attend a gathering of the glittering literati at court. Mahit stands in awe of what to her eyes is the pinnacle of civilization. The gathering doubles as a poetry contest. And as she listens to a recitation of a poem of self-sacrifice at war, which simultaneously spells the name of one of the lost soldiers in the opening glyphs of each line, Mahit realizes that right here, in this very place, is everything she has wanted since she was a young girl back on her home planet at the edge of the empire.

The novel is, not surprisingly, dedicated to “anyone who has ever fallen in love with a culture that is devouring their own.”

Memory Called Empire received the 2020 Hugo Award for Best Novel. It has also gotten some attention from linguists.

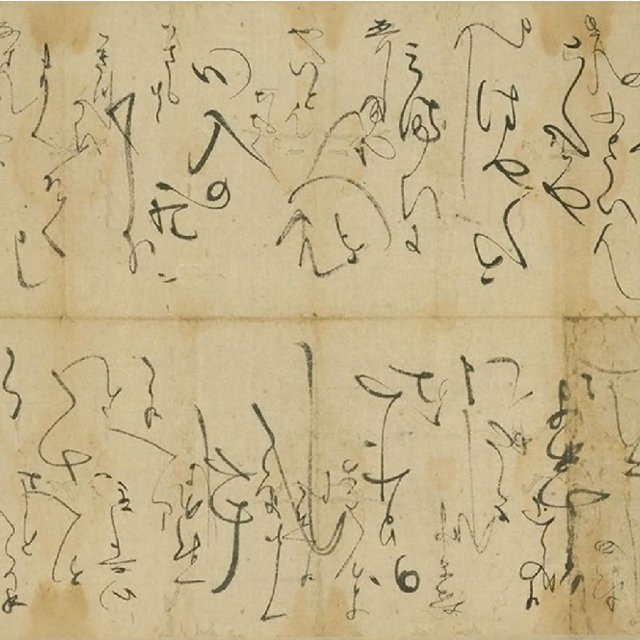

The written language of the empire, Teixcalaanli, is based on the Aztec hieroglyphics of Mesoamerican language Nahuatl, which was the language spoken in central Mexico before the arrival of the Spanish. A logosyllabic tongue written in glyphs like Chinese, the script allows for wonderful poetic artistry and playful wordplay.

I don’t think many students of Japanese language and literature –especially those of classical Japanese—would miss the affinity to the poetry contests and glamor of the Heian court. Reading as protagonist Mahit tries to display her own growing cultural prowess through her ability to make nuanced references to literary tropes, mainly from poetry, it really did feel straight out of the Tale of Genji. According to Martine, in addition to Nahuatl, Teixcalaanli is also inspired by Byzantine Greek. Digging around online, I discovered that poetry contests were a centerpiece of political life during the Middle Byzantine Period (approximately 900-1204 CE), and were used in much the same way as in the Heian court: to prove an orator’s intelligence and cultural competence, as well as to make political arguments.

What do we have nowadays to gain cultural capital? Definitely not impromptu poetry contests at the parties of the powerful.

To read this rest, please see my essay at 3 Quarks Daily

Also: Oracle Bones and Writing in the Time of the Gods神代文字

Nowadays, you show your cultural capital by memeing the latest memes.

Cultured capitals. Now wouldn't that be nice?